Professor Annie Sutherland is a specialist in medieval women’s writing who this year celebrates twenty years as our Rosemary Woolf Fellow in Old and Middle English. She joins us to reflect on what makes English at Somerville so special.

Prof Annie Sutherland in the Somerville College SCR

I think there are lots of reasons why English students flourish at Somerville. One of them is the distinctive ethos of Somerville itself. Our Freshers quickly notice how Somerville feels different to other colleges, less like a castle and more like a home. They still have the sense of joining an institution with a long and illustrious history, but our tutorial rooms and our hall, even our beautiful library, don’t intimidate newcomers. They have a well-loved simplicity, a concern for the essentials of thought, which inspires rather than inhibits confidence.

Our students also benefit from a unique tradition of scholarship in English. As the College’s Rosemary Woolf Fellow, for example, I always teach one of Rosemary’s articles, and tell students my post is named for her. I explain how she was a remarkable and prolific medieval scholar, and they get a real sense of ownership and pride from knowing they’re in a place with a history of people doing important work.

Then there is the atmosphere we create in tutorials. Like Somerville itself, this can be characterised as intellectually rigorous, but fundamentally kind. For me, it’s best captured by the module in Old English I teach to our Freshers each year. The students arrive not knowing each other or Old English, and feeling rather terrified by it all. They pile into my study, where they discover there will always be biscuits, and very often my dog Betsy, and we have fun. We laugh a lot. And yet behind the laughter, driving their progress, is the unspoken knowledge that we’re treating them as equals whose ideas can and should have real power.

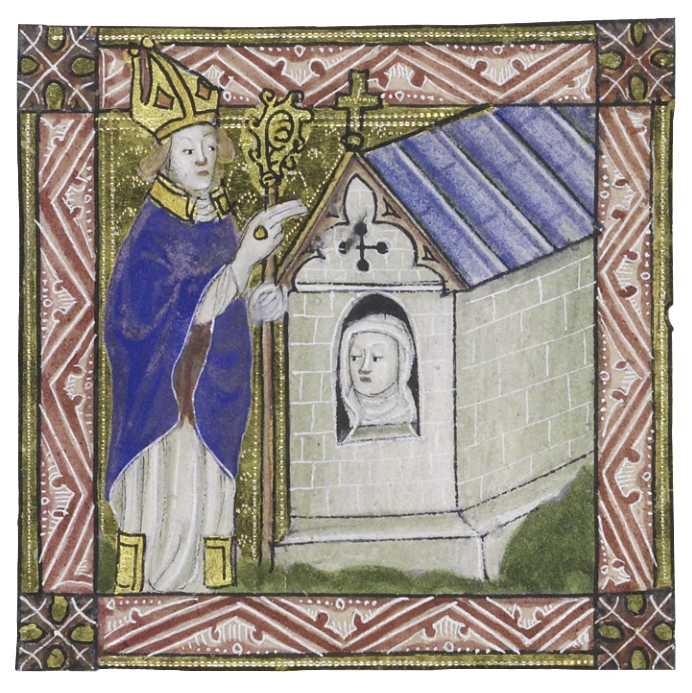

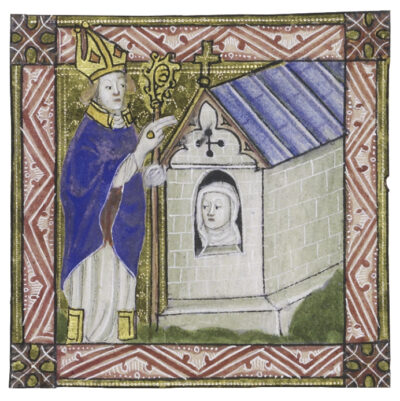

Ancrene Wisse makes for one of those epiphanies which literature does so well, collapsing geographies and time

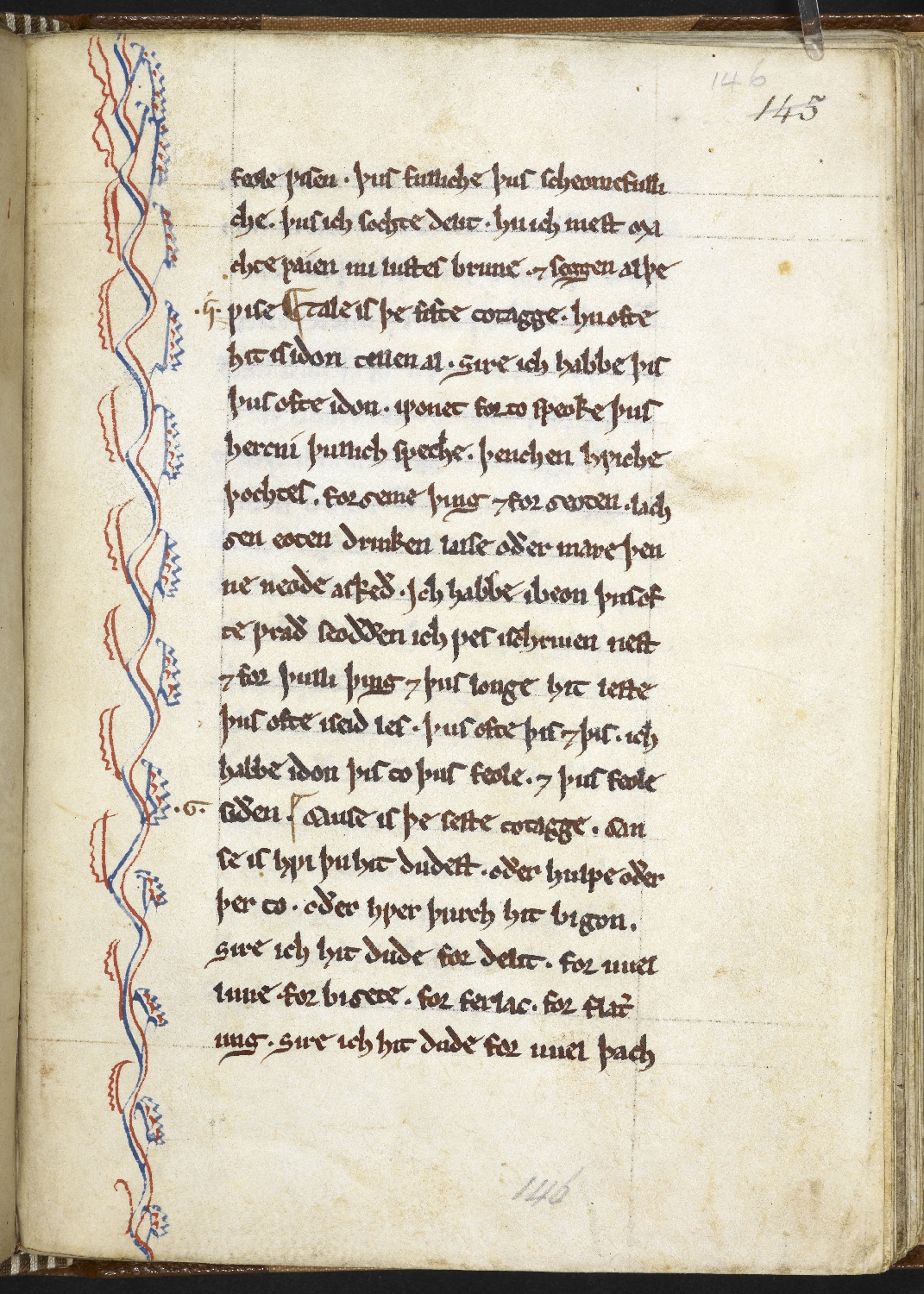

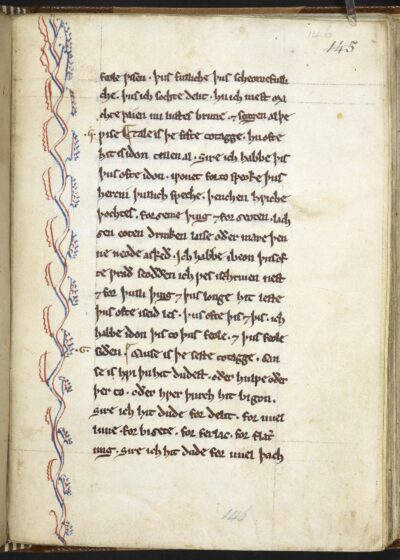

That’s what English is all about, really: the journey towards developing true critical awareness. One of my favourite starting points on that journey is the Ancrene Wisse, a thirteenth-century instructional manual for anchoresses (female religious recluses) written by a male cleric. On first inspection, the Ancrene Wisse sounds rather uninteresting and looks even worse, as it’s written in very early Middle English. But if you read it carefully, guided by someone who knows it well, you realise there’s a huge amount of fascinating, unsettling material there. Students particularly respond to how it engages with questions of gender, is in some ways problematically misogynistic, yet in others gives a lot of agency to its female readers.

Recently, we’ve used the Ancrene Wisse to tease out the analogies between the world of the medieval anchoress and the contemporary discourse around women’s reproductive rights. It makes for one of those epiphanies which literature does so well, collapsing geographies and time, and making students sit up and think, oh my goodness, this text speaks directly to me and my world. By piecing together the similarities, as well as the differences, between the present moment and the medieval world, students gain the confidence to start tracing the other patterns and trends that continue to shape our lives.

For instance, having read the Ancrene Wisse, students go on to read the late medieval anchoress Julian of Norwich. They see how she is proposing ideas that are really very radical, such as the validity of personal experience of the divine, but also how she maintains a constant, self-effacing commentary. Juxtaposing these two elements enables students to recognise that the “I’m not worthy” protestations are really a means of neutralising the radical charge of her ideas; Julian is owning her voice strategically as a means of negotiating the misogyny and problematic power structures of her time in a way that is inspiring, even emancipatory, for students.

Why does all this matter? For me, it comes down to two points. First, by introducing our students to ways of writing and constructing literature, we’re introducing them not only to ideas and schools of thought, but to the fact that people have always worried about the same types of problems. We’ve always been worried about loneliness, about repression and otherness, about the fact that life doesn’t last forever. By confronting this single, inescapable truth, our students learn to think critically, but also compassionately – and we sorely need people who can think like that in today’s world.

Second, our English students learn the equal and opposite lesson of literature which is that, yes, there are obstacles, but if you find your voice, then you can deploy it powerfully. By looking at texts in which not just women, but other marginalised groups and people are presented as having found their voice, we model for Somerville students the importance of taking risks, of being true to oneself and, ultimately, of living a life that has value.

Somerville College is currently seeking to raise £15,000 a year for 3 years to enable the creation of the Anne Hudson Scholarship in Middle English at Somerville, in partnership with the University of Oxford. To support this project, please contact katariina.kottonen@some.ox.ac.uk

This story is reproduced from the 2023-24 issue of the Somerville College Report for Donors. You can read the full Report below.