This is a transcript of the lecture given by College Principal Jan Royall at the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya in Mumbai on December 11th 2018.

Good evening ladies and gentlemen. I know that many of you are here as friends of this glorious museum and my thanks must go to one of your greatest friends, Dr Pheroza Godrej, who made this lecture possible.

It is a pleasure and an honour for me to give a lecture here, surrounded by history in a beautiful environment. I am chair of trustees of rather a different museum, the People’s History Museum which is a national museum based in Manchester. It is the national museum of democracy. We celebrate democracy by telling the story of the struggle to gain our rights and by making it relevant to our lives in the 21st century. The way in which both museums work is very similar, reaching out to people who in the past might not have felt comfortable in a museum. I was deeply impressed when I read of your Sustained Enrichment Programme and I absolutely love your Museum on Wheels. We are both striving to inform the present by learning from the past. Museums can change lives – our current exhibition is entitled ‘Represent’, and includes videos of the maiden speeches in Parliament of two young female Muslim MPs. A few weeks ago one young Muslim girl watching the video actually cried and said, “I did not know that there was a place for people like me in Parliament”.

At Somerville we change lives and this evening I want to talk about changing the world. On our website it says, “If you want to change the world, come to Somerville”. That has been true throughout our history as we have educated and nurtured students who have brought about change – sometimes in their communities, oft times in their countries and occasionally in the wider world.

Throughout my life I have tried to bring about change, especially in relation to equality and social justice. I believe that when we make the most effective changes we stand on the shoulders of those who’ve gone before us. Today I want to tell you about Somerville College, Oxford and its history of extraordinary, pioneering women. I want to talk to you about some of the giants on whose shoulders I am standing. The image comes from a medieval theologian. It was picked up by Isaac Newton, who famously said: ‘If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants’. Newton was right. But my giants are not medieval theologians, or male scientists. My giants are women: sometimes famous, sometimes unsung, each, in her own way, a revolutionary. They are the women pioneers who studied and worked at Somerville College in the University of Oxford, and I am passionate about telling their stories.

I came to Somerville in 2017 as the College’s twelfth Principal. I am proud to say that our line of female Principals is unbroken. I didn’t know very much about Oxford University when I arrived. Naturally I knew it was a great seat of learning, but what does that really mean? To be honest, I found the idea of Oxford a bit forbidding: centuries of tradition: a litany of the names of the brilliant people of history, most of them, it has to be said, white men. Of course, as a member of the House of Lords I was rather used to a place of arcane traditions which had been dominated by white men. But when I got to Somerville, I found something extraordinary: a beautiful space with glorious gardens. Kind, thoughtful people, a great combination of humanity and scholarship, and a level of academic brilliance that’s inspiring. But most of all, an engine of quiet, female revolution.

So what is it, this miraculous place called Oxford. It’s a federation of independent organisations that work together for the benefit of all, to advance mutual interests and shared values, and in which knowledge is accrued and research undertaken which will make the world a better place. The University is made up of colleges, where its students live and work, and where its tutors teach and carry out research. And it also has faculties and departments, where those same students and tutors come together for lectures, meetings, lab work. And then there are the libraries: over a hundred of them. This is Somerville’s: the first dedicated library space in Oxford built for a women’s college. When the College was founded the women were not allowed to use the University’s libraries and those in the men’s colleges were reserved for the men. It is now considered to be amongst the best libraries in Oxford and we have over 120,000 books.

In the First World War, like most of Somerville College, the library was used as a hospital. The celebrated War Poets, Robert Graves and Siegfried Sassoon, were both patients there.

Oxford University is a layered, interconnected place, and every piece of it is about respect for knowledge and learning, and the quest for intellectual freedom. Colleges, in particular, are unusual and wonderful places. They provide an unrivalled, personalized, educational environment fostering interdisciplinarity and a deep sense of community, with a dedicated staff and a vibrant student body. The scale is tiny: Somerville has around 700 students, undergraduate and postgraduate. There are 38 colleges, and what works so well about them is the scale: we all know each other, academics, students and staff. It is a strong and vibrant community in which there is mutual respect. It’s the best of both worlds: a small, supportive environment in the middle of a world-class university of over 23,000 students.

We have the resources and intimate settings for one to one teaching and the financial muscle to carry out world-leading research including scientific research. That’s why we have been judged the best university in the world.

Students come from all over the globe to study at Somerville, 25% of our undergraduates are from outside the UK and over 70% of our postgraduate students. When they get there, they find that at the heart of their academic lives is Oxford’s extraordinary tutorial system. Whatever your subject, you spend at least an hour a week working in groups of two or three with world experts in your subject, talking about your latest essay or working through scientific problems. It’s a powerful form of education. It teaches knowledge, but above all it is an education in learning how to think critically and solve problems. It gives young people the confidence to defend their arguments, to discuss and debate, to disagree agreeably. In an era in which public discourse is becoming less tolerant, this will serve both them and our society well.

If you set out today to design a university from scratch, I’m not sure this is how you’d do it. These layers have evolved over a time and the structure is now hugely complex: living and working in Oxford is like looking at intellectual geology.

Before I get misty-eyed about it, though, let me tell you about who I am: I was born and brought up in the Forest of Dean, a rural area of England on the border with Wales, which is still my home. My Mum was a nursery nurse and my Dad was a chauffeur. Then they ran the village shop before devoting their lives to disadvantaged young people. I studied French and Spanish at the University of London, and I was working as a bilingual secretary when I was drawn into politics. Politics, the British Labour Party and the European Union have since been the constant threads in my life. I even met my late husband through the Labour Party. I worked as the General Secretary of the British Labour Party in the European Parliament. I was special adviser to Neil Kinnock, then leader of Her Majesty’s Opposition, and worked for the European Commission in Brussels for eight years before becoming Head of the European Commission Office in Wales.

I was appointed to the Lords in 2004 and became a government spokesperson on Health, International Development and Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs, then Chief Whip and Leader of the Lords. In the latter position I was a member of the Cabinet and Lord President of the Council, presiding over meetings of the Privy Council. That’s what it says on my c.v. But what does it mean? For me, it’s all about finding ways to effect change.

I come from a family where I was the first generation to go to university. At school, I remember asking one of my teachers about this thing called ‘Oxbridge’ (I thought it was one place. That’s how the British talk about it). He told me I didn’t need to worry about it: I probably wouldn’t be going to university anyway. It was a comment born of England’s very particular class system which I abhor. Of course I did get to university to study languages and I haven’t looked back. Languages, communication across cultures, and finding causes which I can work for, causes that can make a real difference, are the things that motivate me. I am an activist. I want to see greater diversity, greater opportunities for disadvantaged people, more for those whom our global society marginalizes: women, people of colour, the LGBTQI community, refugees. That’s why I’m still politically very much active. I use my position to fight for improvements in education, health and social care, social justice, to campaign against domestic violence and to be an advocate for democratic engagement.

I am proud of my past which has shaped me and given me the values that I espouse. Above all, I believe that an accident of birth should not shape a person’s destiny.

You might not think that those ideals sit very easily with the traditional idea of Oxford but that is changing and Somerville absolutely does not conform to the traditional, old-fashioned idea of Oxford. I feel enormously fortunate to have been chosen as Somerville’s Principal. But I also chose Somerville, because one of the most exciting things about it is how it grasps and engages with the world’s problems, and how it always has done. This is the year in which we have celebrated the centenary of the first votes for women in the UK, and we even designed our own logo for the celebrations.

We have had a packed series of events which looked at how far women have come over the last 100 years and how far we still have to go in order to achieve real equality. Not only is this a moral imperative as we are half of the world’s population and a matter of social justice, it is also an economic imperative.

Somerville was founded in 1879 as a hall where women could live. They could attend the lectures provided by Oxford University while following special courses of instruction, and here it is. The hall was named for Mary Somerville, the nineteenth-century Scottish scientist and mathematician whose research ranged across astronomy, physics and geography. A real polymath for whom the word scientist was coined. Somerville’s founders chose their role model very deliberately: the new hall broke away from the emphasis on Church of England religion which characterized other women’s halls in Oxford at that time.

So, from the very beginning, Somerville was about including the excluded. And that is still our ethos. It would be another forty years before Oxford University granted women the right to degrees at the University, even though those same women had been taking the examinations for those degrees for decades. There was a period when women who passed their exams but who were not awarded degrees travelled to Trinity College, Dublin, where degrees were conferred upon them. They were known as ‘the steamboat ladies’.

One of the steamboat ladies was Emily Penrose, who was subsequently Principal of Somerville. Through diplomacy and determination she helped to right the injustice of women not being granted degrees. Here she is receiving her degree in Oxford on the first day that they were awarded in 1920. Unsurprisingly the fight to gain degrees for women often went alongside the fight to gain votes for women. Penrose herself was a quiet supporter of suffrage, and when some of the College’s more conservative benefactors began to complain that Somerville was getting a reputation as ‘a suffrage college’, Penrose stood firm and allowed meetings of the Women’s Suffrage Society to continue in Somerville.

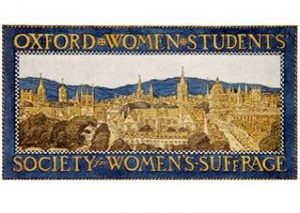

Vera Brittain, the author of the beautiful First World War memoir, Testament of Youth, and one of Somerville’s most famous alumni, saw the gate that the suffrage movement would open: ‘a race or a class or a sex, once liberated,’ she said, ‘never returns to its old condition of servitude’. By 1910, membership of the Somerville Women’s Suffrage Society stood at 75 out of a total student body of 94. Most were non-violent activists, though Oxford and Somerville also had their share of militant suffragettes including Lady Rhondda, a Somervillian about whom a glorious operetta was specially commissioned this year by the Welsh National Opera. In Oxford, the Women’s Social and Political Union orchestrated a campaign of vandalism and even arson but alongside the violence and militancy of the suffragettes stood the peaceful activism of the suffragists. The suffragists fought the same fight, although they were determined to do so within the bounds of the law. It is the suffragettes we tend to remember these days, with their green, white and violet banners and badges. But the suffragists were powerfully important too. They even had their own set of colours: green, white and red. Both sets of colours were deliberately chosen for their symbolism: the initial letters of green, white and red stood for ‘give women rights’; green, white and violet for ‘give women votes’.

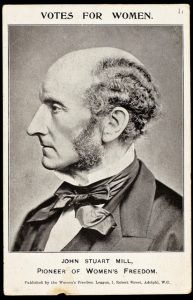

Historians have tussled over the role of the suffragettes versus the suffragists, trying to decide which version of activism was the most successful. My view is that we needed both: the long-term, legal campaigning and the shock tactics. Somerville students raised funds for the movement, and went out canvassing for signatures for the petition for women’s suffrage. And they joined together with others studying in Oxford to found the Oxford Women Students Society for Women’s Suffrage. The aim was to represent what the Oxford women called ‘educated opinion’, and that is what they did. And they also understood the power of the visual, of good PR. This beautiful banner was first used by the society in 1911, and it was designed by Edmund Hort New, the illustrator who worked with William Morris. He also provided the illustrations for the first history of Somerville which was published in 1922.It was no wonder that the petition for women’s suffrage was particularly close to the hearts of the students at Somerville: Mary Somerville was the first signator on one of the first ever petitions for women’s suffrage, presented to the British parliament by the philosopher John Stuart Mill in 1868.

There’s one story I particularly love about one of Somerville’s students and the suffrage movement. Her name was Constance Watson, and she travelled to rural Buckinghamshire to ask for signatures for the suffrage petition of 1909. Her experiences were typical of those of us who have worked as activists: she noted that alongside ‘the Absent’ there were also ‘the Abusive’ and a large batch of people who said, “I haven’t heard much about it”. But she also met those she called ‘the Angels’: ‘the blacksmith,’ she said, ‘who put his head out of the window and asked for the petition… and the elderly woman who, on hearing about the petition, said “Why of course… of course I want the vote if I can do any good by it”; and she promptly put her cross on the petition’. The sting in the tale is that that woman’s ‘cross’ would not have counted: she couldn’t write her name which meant she couldn’t be counted. But her instinct for social change was everything any of us could hope for: not only bold, but selfless: ‘of course I want the vote if I can do any good by it’.

I am a firm believer in the power of voting to bring about change and I have great admiration for India, the world’s biggest democracy. Democracy cannot and must not be taken for granted – it must be nurtured through participation and education.

Education transforms lives and transforms society. It is the means by which we can transform the quality of life for people all over the world. It provides a ladder from deprivation to opportunity. It enables individuals, societies and countries to succeed and to prepare for the future. It is a means of finding ways to bridge current divides in our societies and our world, and a means of prevent future divisions.

For me, that is what Somerville is about: education, and using education to bring about change. As I got to know Somerville, I began to learn about the women who had studied there and who had brought about change. I had the uncanny sense that they were soulmates, sisters in activism.

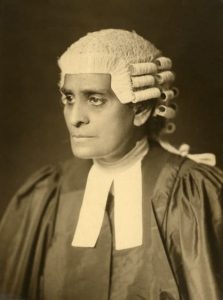

Cornelia Sorabji, the first female advocate of Law in India and the first woman to study law at Oxford

The roll call of extraordinary women from Somerville is a long one: lawyers, scientists, authors, classical scholars, public servants, politicians. I could have chosen any one of them to talk about this evening and kept you here for – until midnight at least. Cornelia Sorabji , the first woman to study Law at Oxford, one of the first women in India to be called to the Bar, and the first woman ever to practise law in India and in Britain. Bamba and Catherine Singh: the Indian princesses who were part of the suffrage movement.

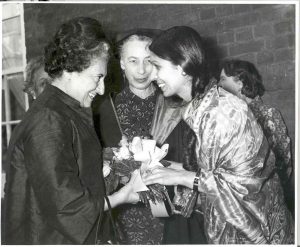

Emily Penrose: the classics scholar who persuaded Oxford University to grant degrees to women. Eleanor Rathbone, the first Somervillian to be elected a Member of the UK Parliament, who spoke out against female genital mutilation and campaigned for women’s rights including women’s rights in India. Vera Brittain, who bore powerful witness to the generation ravaged by the horrors of the First World War. Indira Gandhi, of course: India’s first woman Prime Minister. An extraordinary woman, and hardly a figure without controversy. Here she is, visiting Somerville in 1971. Last week I had the honour of hosting a lunch for an eminent Classicist, Joyce Reynolds, to celebrate her 100th birthday. And one of the photos we found to show her was of her matriculation in 1937 and, lo and behold, Indira Gandhi was in the photo.

While we’re on the subject of controversial figures, Somerville’s most famous daughter was Margaret Thatcher: the first woman and the first scientist to be Prime Minister the United Kingdom. On the other side of the British political spectrum, Somerville boasts Shirley Williams, the Labour then Liberal politician who fought to establish comprehensive schools and who has rightly been called the greatest Prime Minister Britain never had. Dorothy Hodgkin, the only British woman to date to win a Nobel prize for science, and Janet Vaughan, whose work on blood transfusion saved countless lives in World War Two and led to the blood transfusion service.

It could be an intimidating list – it could make you feel that you couldn’t ever measure up. But as soon as I arrived at Somerville, I felt something quite different. I felt that they were helping me: their values, and this amazing place that they helped to create and sustain, reaching out to me across the generations. So what do they have in common, these extraordinary individuals? Certainly not their politics: although most of them were progressive, if we were to get them all together in a room I think the arguments would be long, fascinating, and pretty heated! For me, what they have in common is an inspiring combination of idealism and practicality. They knew that change was needed, and they worked to bring it about. What’s also so powerful about the women pioneers of Somerville is their intelligence, their practicality, their good sense, their humanity and their determination. I am now going to introduce you to three of those women and talk about how they have inspired me.

Cornelia Sorabji – I’m ashamed to say that when I came to Somerville, I had never heard of Cornelia Sorabji. Very few in the UK have, although we are aiming to change that. Of course, she is better known in India, but for my money, still nowhere near as well-known as she should be. She was born in 1866, one of eight children (including seven daughters) of a Parsee family of Christian educationalists.

As a child, Sorabji found herself moved by the appalling life stories of the women who lived behind the ‘curtain’ of Purdah. She learned how their enforced seclusion was often compounded by illiteracy, making them easy victims of legal fraud when it came to their rights and property. When her mother asked her ‘What are you going to do for India when you grow up’, she decided that the most practical way she could help was to learn the law.

Sorabji’s life story is a series of firsts: she was the first woman to study at Bombay University, where the male students slammed the doors of the lecture hall in her face, but where nonetheless she went on to win a first-class honours degree: the first woman to be admitted to read Law at Oxford University. She was, without doubt, exceptional. For me, the story of how she came to Oxford epitomizes the values of Somerville. The person who came top of the examination lists in Law at Bombay University was automatically entitled to an Indian Government Scholarship to study Law in the UK. That is, until it was discovered that she was a woman. She was denied her scholarship, and it was only after the first Principal of Somerville joined together with other social activists, including Florence Nightingale, to raise the necessary funds that Sorabji was able to take her place. She was Somerville’s first Indian student, though she was quickly joined by the Duleep Singh sisters, Catherine and Bamba. And here they are, the three of them, in the 1891 Somerville College photograph. I find the photo fascinating and instructive.

The Duleep Singh sisters, sitting in front of Sorabji: remarkable women: particularly Catherine who was an active suffragist, and she also blazed a trail in another way, living with her female partner. But it has to be said that the Duleep Singh sisters had hardly struggled in their early life, at least socially and economically: they were princesses (their father, Maharaja Duleep Singh had been deposed as ruler of the Punjab in 1849). And if you had to guess, which of the three women sitting in the corner of this photograph is the one with the real fight, grit, determination in her, you’d have no trouble guessing, it’s Cornelia. She’s guarded, and she looks wonderfully fierce. She needed to be. Somerville might have welcomed women, but Oxford as a whole was still hostile. The University tried to refuse to allow Sorabji to sit her examinations in the Examination Schools building alongside the male students. She objected, but it was the only the intervention of the famous classicist Benjamin Jowett of Balliol that made a difference. The University Council spoke and said, ‘Oxford shall examine Cornelia Sorabji’.

It’s a wonderful story and it doesn’t end there. When she finished her degree, in 1892, Sorabji returned to India and fulfilled her promise, working with women in Purdah, and not just in the legal sphere. Sorabji spent the better part of her life working to improve health, social care and education. She also reported on social conditions, keeping the issues of women in Purdah firmly on the agenda. Somerville was important in her life, but I am proud to say that she is also vital to Somerville’s current life and development. Oxford and Somerville and the Indian Government joined together to create a scholarship programme for talented Indian students of Law. Based at the Oxford India Centre for Sustainable Development at Somerville, the Cornelia Sorabji Graduate Scholarship Programme has been made possible through generous donations from Somerville alumni and members of the legal community. Launched in 2016, the Sorabji scholarships aim to support students who would not otherwise be able to afford to study at Oxford, and they are expressly targeted at those who seek to lead change on their return to India.

The Sorabji scholars are hugely inspiring: a new generation of Somerville pioneers. Here are the first two holders of the Cornelia Sorabji Scholarships: Divya Sharma and Navya Jannu. Let me tell you about just one of the current scholars, Aradhana Vadekkethil who came to Somerville after studying at National Law University Delhi, and is working for a postgraduate degree in Law. She remembers reading Cornelia Sorabji’s work and, she says ‘feeling her sheer determination to liberate women’. Aradhana works on the intersections of gender, class and caste as they relate to crime and violence. She’s volunteered as part of a project on the death penalty in India, and to hear her speak about her work on the death penalty, on rape and the legal concept of consent, and on LGBTI issues, is to hear the echo of Sorabji’s passionate fight against injustice.

At Somerville, we are especially proud of our strong and flourishing ties with India, and those ties are not only about our past but about the future. In Somerville, India is a focus of intense interest for our tutors and our students. Our events with the Oxford India Centre are some of the most popular in the College, and always guaranteed to produce vigorous debate and discussion. The Centre enables researchers to translate academic ideas into policy initiatives with the power to change people’s lives in India, as well as supporting exceptional Indian scholars to study at Oxford.

The range of approaches and topics is inspiring. Earlier this year, we hosted a seminar in which policy-makers and academics debated the lessons for water security and looked at the story of irrigation reform in Madhya Pradesh. Our brilliant scholar Ranu Sinha has worked closely with the chief civil servant in Madhya Pradesh in charge of water and has helped to transform irrigation and consequently agriculture in the state. In February, we hosted a discussion on the future of UK-India relations in a post-Brexit world. The themes that emerged were ones that I am passionate about: the need for an energizing fusion of individual action and collaboration; the importance of a free exchange of people and ideas between our countries. It’s no secret that I am watching the approach of with great trepidation and real sorrow. I think of myself as a citizen of the world and, especially, as a European. I fear for the economic and social future of my country, at least in the short term. The Brexiteers believe that as India’s economic success and influence grows Britain will be in the front line to share in that success through partnership. Of course I hope that she will be, but I am a realist.

I am confident, however, that the scholarships that we have at the Oxford India Centre will continue to increase. In 2013 we started with 3 scholars and we now have 14. My intention is that we will have at least 20 in the next couple of years. These represent a real partnership between our two countries, enabling the brightest young Indian students to acquire knowledge and undertake amazing research in the best university in the world, then returning to India to turn the research into practical policies that will make a difference. Cornelia’s mother spurred her into action when she asked her: ‘What are you going to do?’ More than a century later, Cornelia’s story is spurring other young people into action, and her legacy equips them to bring about change.

Janet Vaughan – My second Somerville giant is Janet Vaughan, one of my predecessors as Principal. When she arrived as a student at Somerville she said she had only ‘a little ladylike botany’ under her belt. I’m not sure I believe that: she was famously self-deprecating, but it is true that one of her headmistresses had once told her she was too stupid to be worth educating. There’s that story of discouragement again, all too common for women. She proved that teacher wrong by coming to Somerville and taking a first-class degree. She then trained as a doctor, practising medicine before coming back to Oxford to work as a research pathologist. When first qualified she worked in the slums of East London where there was great poverty and she became a life-long socialist.

It was during the Second World War that Vaughan developed a system for separating, storing and moving blood that saved countless lives and continues to do so. Modern blood transfusion was effectively invented by Janet Vaughan. She herself once used an innovative transfusion technique to save the victim of an air raid, a child – and that child remembered Vaughan’s name and later decided to study at Somerville. At the end of the war, Vaughan was asked to go to Belsen to carry out research into how those suffering from starvation could best be fed (‘I am here,’ she wrote in a letter home, ‘trying to do science in hell’). She was one of the first people into Belsen and her experiences only spurred her on to more scientific work. When she returned to Oxford as Principal of Somerville she continued to work in the lab and write academic papers, only stopping well into her 80s – a college play portrayed her crossing and recrossing the stage, murmuring ‘Just off to the lab, just off to the lab…’.

Vaughan was the first scientist to be Principal of Somerville. She was also, for a time, the only scientist head of any Oxford college. Under her, science developed even further, into one of Somerville’s great strengths, and by the time she left office, 40% of the College’s undergraduates were studying mathematics or one of the sciences. It’s pleasing to think that a member of Somerville in the 1940s, 50s and 60s might have been puzzled by today’s concerns about the place of women in science: it must have seemed to them that the College was the place of women in science. These days, as a mixed College, we have many students studying science but still not enough young women. And the number of women Professors in Physics and Chemistry is shameful. We have much work to do.

Vaughan’s interest was not only in science, but in excellence no matter the subject, and she encouraged the great and the good in all disciplines to visit the College – this was the time when Wittgenstein could be seen visiting the Senior Common Room as a guest of Research Fellow and celebrated philosopher Elizabeth Anscombe. She also planned the first dedicated accommodation for postgraduate students in Oxford and started the first proper services for student health. Her sheer level of energy and output was prodigious, and made her a profoundly influential role model for generations of Somervillians. When she was once asked in a radio interview how she managed to fit so much into her life, Vaughan said simply, ‘I never played bridge’. I love her, and I think she offers lessons for us all.

I hasten to add that I don’t play bridge!

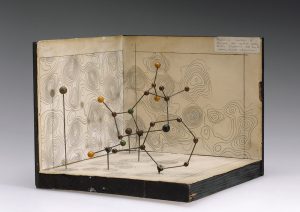

And last but definitely not least in my trio is Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin, listed in the Guardian newspaper as one of ‘five amazing female scientists you’ve probably never heard of’. Well, if you haven’t, you’ll want to. She studied Chemistry at Somerville, and then went on to do PhD research in Cambridge before coming back to Somerville to take up a Fellowship – to be teacher and researcher, in other words – in 1934, becoming its first Tutorial Fellow in chemistry in 1936.

Her work was in in X-ray crystallography, and it went on to become a powerful tool for investigating biological molecules. With it, Hodgkin was able to reveal the structure of insulin and of vitamin B-12 and she also solved the structure of penicillin. It was this groundbreaking research that led to her winning the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1964. A remarkable accolade for a remarkable woman but a woman’s place was still deemed to be in the home. The 1964 headline in one British newspaper that announced Hodgkin’s achievement read: ‘Oxford Housewife wins Nobel Prize’. And here are some of the others:

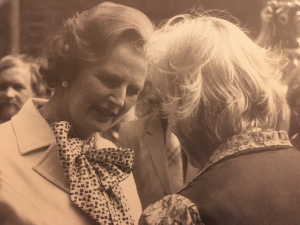

Hodgkin’s scientific work was groundbreaking. That much is obvious. But Hodgkin was also an activist, and a woman who took practical steps to improve the world. She was a supporter of nuclear disarmament, and she took care to make sure that she set out her views to the powerful, even when there seemed little chance that it would make a difference. One of her students was Margaret Thatcher who read chemistry and they remained in contact even when Thatcher became Prime Minister: here they are in Somerville. Hodgkin would go to Downing Street to visit and I am told by one of Lady Thatcher’s closest advisers that Dorothy was the only person of whom she was afraid. She would frantically read scientific periodicals in an attempt to prove to her former tutor that she was keeping up. Hodgkin would then explain her views on disarmament to Thatcher. It’s that Somerville tradition: believe in something, explain it clearly and intelligently, and have respect for the views of others, even when you disagree.

Hodgkin was another person of ‘firsts’: she was the recipient of the first ever maternity pay in Oxford, which was specially arranged by Somerville’s then Principal, Helen Darbishire, to ensure that Hodgkin could continue to work alongside family life. The importance of that practical support was not lost on her, and in a wonderful gesture, Hodgkin used a large part of her Nobel prize money to fund the establishment of a crèche in Somerville, so that other tutors could the balancing act of professional and family life. Somerville has always been like that: when a need is identified, the College takes action. In the 1930s, the same Principal who later arranged maternity pay for Hodgkin was at the forefront of offering academic posts and accommodation to Jewish refugees from Germany: this is one of them, Lotte Labowsky, who went on to become Somerville’s Librarian. For me, the lesson from these brilliant women is that a true pioneer doesn’t just talk about the need for change: they get it done.

As I said at the start of the evening: I am an activist. For the whole of my life, I’ve wanted to create change to make the world a better place. I’ve been championing the causes that matter to me for forty years now, and at Somerville I’ve found the inspiration to do even more. One of my missions is to do more to include the excluded and Somerville is at the forefront of initiatives to increase access for those who wouldn’t traditionally look to come to Oxford.

We offer summer schools, scholarships and support at every level. Year on year, we are increasing the proportion of students at Somerville who come from non-traditional backgrounds. It’s something I am passionate about, and I want to see more of it. When I speak to our students, I hear so many versions of the same story: the teacher or relative who said that Oxford wasn’t for them. It’s my story too, and I feel it’s my responsibility to use the privilege of my position to make sure that story becomes history. And I also see my responsibility playing out in another way. I want Somerville’s students to be able to stand on the shoulders of giants. I want them to know about the extraordinary individuals who have gone before them, and to draw strength and inspiration from them.

Our students are inspirational. As you will see from this photograph of some students at an open day, wearing the t-shirts they’d designed for themselves, they have embraced our ethos of putting words into action to bring about change. They are working with prospective students giving them information, aspiration and confidence to apply to Somerville, no matter their background, their community, their culture or their country. I am delighted that 30 of our students are here with us this evening. They are members of the Somerville Choir, the first Oxford Choir to visit India, and I hope that many of you will be able to attend their concert at the NCPA on Thursday. They are also doing outreach work with the charity, Songbound, and with the charity Karta, taking action to change lives.

I believe that the women pioneers would have been proud of the students who are following in their footsteps. Alongside their studies, their entrepreneurial attitude to social change is inspiring: last year, a group of students and young alumni from Somerville used our crowdfunding platform to raise the money to buy and install six new computers for Roshni Matriculation School, part of a wider project supporting women and girls in Chennai. A second group of Somervillians is involved in a charity startup, using technology to help the homeless in Oxford by creating an innovative app as part of a city-wide support scheme. One of those involved in ‘Greater Change’ said ‘This project has such clear ties to Somerville, and fits right in with the ethos of the college. It’s innovative, exciting and will make a real difference to the world and to individual people’s lives’.

I think that’s a perfect description of Somerville, both now and throughout its history: innovative, exciting, and making a real difference.

The Somerville Junior Common Room supports Roshni, an NGO that runs a school in Chennai and supports women’s initiatives across the city.

The students I meet every day give me great hope for the future and this is needed in our difficult and complex world which thanks to technology is more connected yet because of populism and protectionism risks fragmentation and disintegration. The challenges faced by their generation are enormous, including climate change, international terrorism and migration, but it is to them that we must look for solutions to these problems. I believe that the education that the enjoy, the intellectual rigor that they develop, the knowledge that they accrue and the research on which they embark at Somerville will enable them to confront our global problems and transform our societies to meet the challenges of the 21st century. Like me they are standing on the shoulders of giants, the women pioneers, gaining inspiration and strength from our radical history.

Universities are places where we respect cultural differences, where we embrace the clash of ideas. We argue fiercely with each other but resolve our differences in a spirit of compassion and understanding. That is crucial at a time when it feels as if the world is growing darker – fear of the other and intolerance dominate where there should be hope.

In what seems to be a dark time, Somerville and Oxford are beacons of tolerance, equality, internationalism, liberty and freedom of speech. And I feel very proud and fortunate to see all of you here tonight, and know that we have such good friends in India, who share our belief in tolerance and liberty.

Our two countries and our societies face great change, much of it swift – for example, Oxford Economics recently reported that in the next two decades, the 10 fastest growing cities in the world will be in India. But whatever challenges our two countries face over the coming years, economic, social or in terms of sustainability, we must work together to solve them. Together, inspired by pioneers like Cornelia Sorabji, we will build a more progressive future. We owe it to those whose shoulders we are standing on as well as to future generations.