In the aftermath of the company’s collapse, writer Jane Robinson (1978, English) reflects on Thomas Cook’s pioneering role in opening the world to British women.

“The only use of a gentleman in travelling,” wrote adventurer Emily Lowe in 1857, “is to look after the luggage, and we take care to have no luggage.”

She and her mother had just completed an outlandish trip – Norway – and were understandably proud of their independent spirit. Men fussed and blustered so on holiday; they were overbearing and embarrassing. Much better to leave them at home and be free.

Emily and Mrs Lowe were ahead of their time in travelling ‘unprotected,’ as she put it. It was still considered outrageous for ladies to venture abroad without the guiding hand of a husband or brother. Abroad was a dangerous place. Alone, among foreigners, they might easily get lost; lose their heads, their money or even their virtue. And if prepared to risk all that, then they probably weren’t real ladies at all.

There was one way, however, to avoid censure as a lone Victorian woman traveller, and that was to join the burgeoning band of Cook’s tourists. Thomas Cook, his son John Mason Cook, and his unimpeachable, smartly-uniformed staff accompanied women unable or unwilling to provide their own male companions.

The company built its reputation on its founder’s trustworthiness. His well-known sobriety as a family man; his professional expertise and engaging, ultra-respectable manner made him a perfect chaperone at a time when most women were hardly allowed beyond the drawing room without supervision.

Thomas Cook was a Derbyshire lad, born in the village of Melbourne in 1808. At ten, he was apprenticed to a market gardener; later he worked as a wood-turner, a printer, and a lay-preacher in the Baptist Church. As a temperance campaigner and a natural entrepreneur he developed a mission to distract other working-class people from the demonic temptations of drink.

That’s how his very first excursion came about in 1841, when he arranged a trip on the new-fangled railway from Leicester to Loughborough – some twelve exhilarating miles. Five years later, 350 excursionists set off with him to Scotland; gradually he and his growing business extended their reach to the Continent, Egypt, the US and – from 1872 – around the world.

To keep his clients informed, Cook published a house magazine, The Excursionist, from 1851 onwards. A complete run forms the core of the company’s precious archive. There are notices of forthcoming tours, features about current and future destinations, travel book reviews and – best of all – hundreds of advertisements aimed at women.

Not just for respectable hotels, but an eclectic array of crushproof hats, waterproof boots, exotic hair-preparations, knapsacks, pop-up hammocks, a Neuro-Therapeutic cure for sea-sickness, a device to jam under a hotel door from the inside to make it impossible for outsiders to get in, and a portable rope-ladder for night-time escapes from burning buildings.

Travellers’ tips feature heavily, with advice on what to wear abroad to combine practicality with style. Victorian ‘globe-trotteresses’ did have a reputation for looking eccentric or depressingly frumpy, a characteristic Cook’s were keen to address – with some success. In 1889 a popular travel-writer was able to claim with relief that ‘the days are, happily, now long past when the cherished tradition of the Englishwoman, that one’s oldest and worst garments possessed the most suitable characteristics for wear in travelling, excited the derision of foreign nations, and made the British female abroad an object of terror and avoidance to all beholders.’

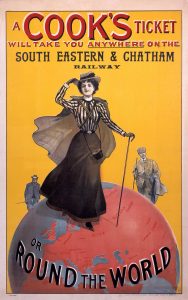

Later editions have at their masthead an Edwardian lady striding the globe: Thomas Cook was a canny businessman, and knew his potential client-base in the leisure industry he invented. He was a pioneer; the man who opened up the world to ordinary people. That’s why it is so important that his legacy should not be lost, either materially, in the form of the company archives, nor ideologically. He inspired and educated, kindling that little flame in all of us to see beyond the horizon – even women.

Jane Robinson is a writer specialising in social history through women’s eyes. The first two of her eleven books, Wayward Women and Unsuitable for Ladies, were inspired by her work in the Thomas Cook Archives.