Jean Toynbee, née Asquith, is 103. She recently met with Jackie Watson, joint Secretary of the Somerville Association, to consider how a life spanning a privileged upbringing on the edge of the aristocracy to GP practice in Cowley and building a family in Yorkshire reveals much about Somervillian strength and adaptability, and reflects many of the changes of the past century.

A large part of the joy in my new job is meeting alumni and learning about the impact of their time at Somerville. Some have loved College, and built directly on what they studied here; others had more difficulty at that time of their life, and their paths have been less direct. But all comment in our conversations on both academic and personal qualities they developed as a result of their Somerville years.

I was invited earlier this year to visit a rather wonderful woman whose experience of Somerville began as she arrived to begin her degree in 1940. In the midst of World War Two, Jean Asquith came up to College to read History. Two worlds clashed around her: the brutal and disruptive reality of wartime England, and the calm privilege of her early life.

Childhood

The second daughter of Brigadier-General Arthur Asquith and Betty Manners, and grand-daughter of former Prime Minister, H. H. Asquith, Jean was born on 6 November 1920, and her young life was full of the advantages of being born into a wealthy world. She clearly loved horses – as did many others in her family – and became a passionate rider. Reputedly inspired by Jean’s passion for horses, her mother’s friend, author Enid Bagnold, wrote the famous novel, National Velvet, later turned into a Hollywood film with Elizabeth Taylor. Travelling for family holidays to Clovelly, in Devon, involved taking the horses there on the train too – a story the 103-year-old Jean still tells with a sparkle in her eyes.

A young Jean Toynbee on the right, with her two sisters and her mother, Betty Manners. © National Portrait Gallery, London

Like many young women born into wealthy families in the inter-war years, Jean did not attend school. There were governesses at home, most notably Lytton Strachey’s niece, Julia (later a novelist in her own right), who went with them to Clovelly one winter. But going to Oxford was not the obvious route for young ladies of this background. Being a debutante, like her elder sister, Mary, was expected of Jean too, and she too was presented at a ‘coming out’ ball. In Jean’s own words, ‘Mary had loved every moment and of course never lacked partners. She was passionately sociable by nature…’ But the young Jean had always known her own mind and her ambition was not to follow her older sister: instead, it was to follow the path of her father, who had studied at New College before World War One. On his deathbed, he had drawn a promise from Betty to let Jean too go to Oxford, and a scholar from Somerville, Phoebe Poole, was hired to tutor the eighteen-year-old.

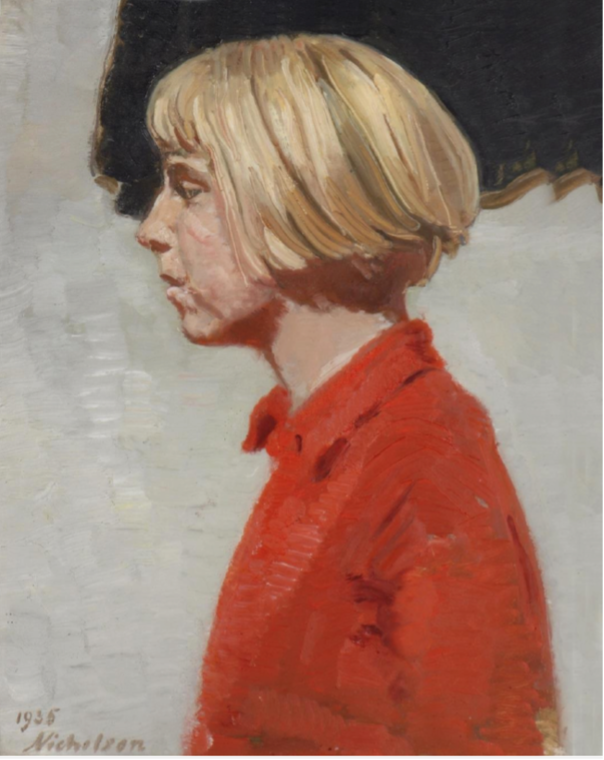

A 1935 portrait of Jean by William Nicholson. Nicholson had originally been asked to paint Mary, but found the characterful younger sister more appealing as a subject.

VAD and Somerville

Phoebe Poole was obviously good at her work, and Jean Asquith arrived at Somerville in September 1940 to read History. This, however, was not quite what she planned to do.

It was 1940, and she had been volunteering as a VAD (Voluntary Aid Detachment) nurse in London just before she went up, just as, in the First War, women such as Vera Brittain had done. Although Jean is self-deprecatingly humorous on the topic of her VAD work, and talks of changing the flowers more than dressings, clearly the work was hard – especially for a young woman brought up as Jean had been. She and her friend June Osborne worked at the Royal Northern Hospital in Holloway Road, with only horse hair to clean up patients’ bottoms as paper was at a premium. She has a memory of a young Jewish woman who had arrived in London on the Kindertransport and was also volunteering in the hospital. Being told off publicly by the all-powerful matron, the young woman had returned home that evening and had committed suicide, by throwing herself down the stairs. Such experiences are not easily forgotten.

In 1940, undoubtedly, Britain needed more medics. On arriving at College, Jean met Dorothy Hodgkin, and the rest, as they say, is history. She changed from History to Medicine – having never had a science lesson in her life – and though this was not easy, she completed her degree with determination, and some resits, and went on to become a doctor. She talks animatedly of her time living in House, and of tutorials with Hodgkin, who was quiet, focused, and clearly had a great mind, though, Jean felt, was not easy to befriend.

On a personal level, she also remembers meeting her future husband, Lawrence Toynbee, at a dance in the Town Hall. Getting back to College late (a veil is drawn over whether she needed to climb in over a wall: it was after 11pm!), coincided with a Physics exam she did not pass, and she went down for a term, returning to resit and to succeed. As she remembers it, both learning the science and – perhaps even more – the jitterbug on the blind date with Lawrence were worth it!

Remembering completing her training at the Radcliffe Infirmary in Oxford, Jean notes how differently you were treated as a qualified doctor as opposed to a student. That all-powerful matron was now deferential. Jean compared the transformation as changing from a pupa to a butterfly.

Marriage, Medicine and Yorkshire

Marriage to Lawrence in a side chapel at Westminster Cathedral was followed by the appearance of six daughters. Married life after the war began in Oxford, and they bought a house on the Woodstock Road, while Lawrence, after a course at Ruskin, taught Art at St Edward’s, and Jean became a part-time GP in Cowley. Using her skills to benefit a diverse community around the car plant, this was a happy time when her daughters were young. Memories of swimming in the school’s open-air pool and of the excitement of Churchill’s coffin passing close by on a train en route to Blenheim marked this period of activity and family life.

Of the six daughters, three (Rosalind, Clare and Rachel) were to follow Jean to study at Somerville (though to study English not medicine), and so was the daughter of a fourth (Elisabeth, Celia’s daughter and Jean’s grand-daughter, who read PPE). Meanwhile, the family moved north, into the beautiful countryside close to Castle Howard, and Lawrence went on to teach at Bradford School of Art, including David Hockney amongst his students.

Somervillians of 3 generations: January 2024

Thus it was that a family of Somervillians asked me to lunch in North Yorkshire one Sunday in January and I had the real pleasure of learning about Jean’s long life: lived alongside the bigger events in the history of the last century. We think she may well be the oldest living Somervillian. But, as Esther Rantzen famously used to say, that’s unless you know different!