Annie Sutherland, fellow and tutor in Old and Middle English, has given a series of lectures about the resonances of the medieval in the modern. Here, she writes about medieval religious iconography in Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale.

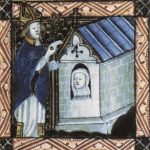

In my own research, I work specifically on women called anchorites, who were like hermits, but the difference is that they lived a life of strict enclosure. A hermit could wander around but an anchorite was literally bricked in to a small room, attached to a parish church.

A lot of the language that Margaret Atwood uses when talking about the experiences of women in Gilead – her fictional theocratic state – has resonances with the literature of guidance written for anchorites – cultivating fear of what is outside the enclosure, a view of women that reduces them either to walking wombs or temptresses.

I am thinking specifically of Aelred of Rievaulx’s 12th century De Institutione Inclusarum, where he states:

Beware of your weakness and like the timid dove go often to streams of water where as in a mirror you may see the reflection of the hawk as he hovers overhead and be on your guard.

(De Institutione Inclusarum, line 603ff)

There is an obvious parallel here with Gilead’s reliance on the threat of violence for the maintenance of order. Speaking, for example, of her re-education in the Red Centre prior to her deployment as a handmaid, the narrator Offred observes:

The guards weren’t allowed inside the building except when called, and we weren’t allowed out, except for our walks, twice daily, two by two around the football field which was enclosed now by a chain-link fence topped with barbed wire. The Angels stood outside it with their backs to us. They were objects of fear to us … (The Handmaid’s Tale, I ‘Night’, chapter 1, pp. 13-14)

Atwood’s modesty costumes were developed from religious iconography. She has this brilliant line about Aunt Lydia – one of the women who indoctrinates the handmaids – wanting the women to “look like something Anglo-Saxon, carved on a tomb, or Christmas card angels, regimented in our robes of purity.”

I am interested in the handmaid’s costume, and what I am particularly interested in is the fact that in contemporary America, the handmaid’s costume is worn by women as sign of protest against rigid misogyny.

A costume that was intended to symbolize female subservience and disempowerment takes on a subversive meaning in the contemporary western world – the images of women going to protest Supreme Court confirmation hearings.

As 21st century women, we struggle to understand the anchoritic lifestyle and we see it as disempowering and symptomatic of a society which despises women.

I feel that part of my responsibility as an academic is to engage with the past on its own terms and try to understand the motivation of women who entered this anchoritic life.

The wearing of costumes as symbols of empowerment and protest encouraged me to think of the ways in which these medieval women regarded their own enclosure.

Looking at the literature and visual art associated with anchorites, it seems possible that what looks to us like oppression was in fact experienced as liberation.

Enclosure may well have been empowering. It allowed women to focus, removed from the distractions of world. It was unusual for any women except the wealthiest to have access to their own time in the medieval world.

I am not suggesting that anchorites were like the women in Gilead. But the re-appropriation of the handmaid costumes in contemporary America encourages us to think again about anchorites.

The architects of Gilead thought: if we shut women away we will disempower them, they won’t rebel, they won’t cause any trouble.

They had a really inadequate understanding of what the results of their experiment would be. The medieval understanding of enclosure was much more subtle than that. They recognised female agency and respected female intelligence.