Last August, Somerville Chemistry student Liam Garrison embarked on a trek across Spitsbergen. Liam was the photographer and filmmaker in a team of five who skied for 30 days across the island off the Svalbard archipelago.

‘Spitsbergen Retraced’ mirrored an Oxford University expedition that took place 93 years ago by following the same trek and geological mapping, conducting the same surveying and capturing the same photos. You can read more about Liam’s preparation for the expedition here.

The team raised £10,000 through Somerville’s crowdfunding platform, which went towards the team’s guide, boat transport, sledges, research equipment and production of a film that Liam shot and is currently editing alongside team member Jamie, a third year historian at St Hugh’s College, and Martin Williams, an Emmy and Bafta winning executive producer. For regular updates on their progress and additional photos you can visit their website, Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.

Liam Garrison reports:

Despite some rather questionable weather (we were caught in a couple of serious storms), we have had a fantastic thirty days following in the footsteps of the 1923 expedition. As well as successfully retracing their route traversing the ice cap we secured repeats of over twenty original photographs.

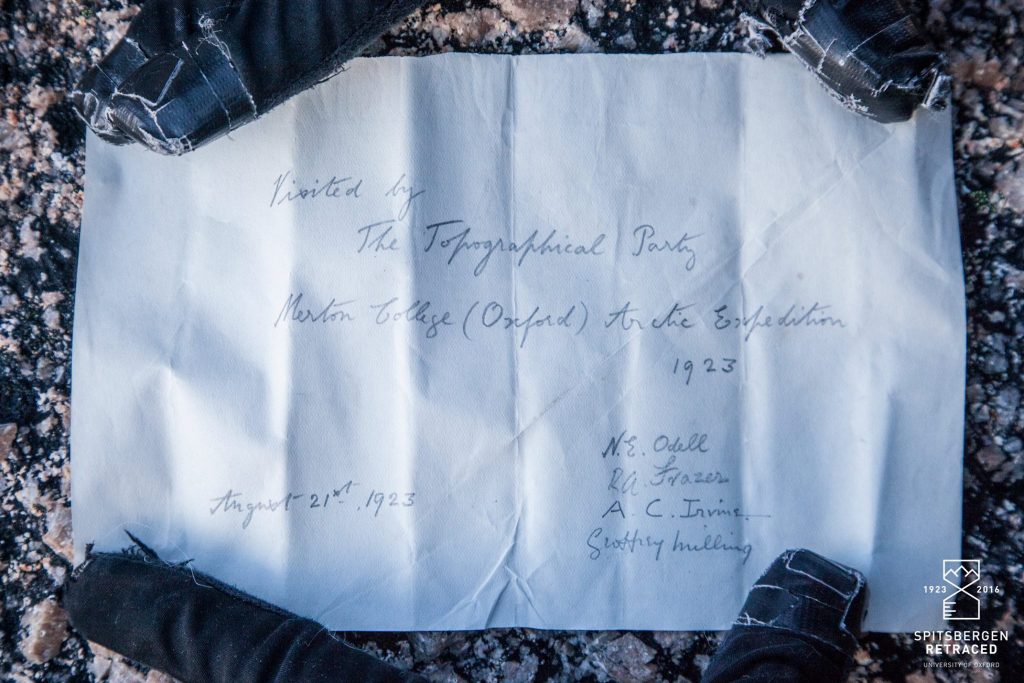

Particular highlights from the history included discovering remains of the 1923 ‘Carpet camp’ and a note signed and cached on Mt Chernishev by the original team to which we have added our own.

The expedition also proved fruitful on a scientific front. We conducted DNA sampling of a number of vascular plants and drone-mapped several transects on the Bear Bay Glacier.

Lastly, the team enjoyed several good days of mountaineering. Notably, we made a first ascent of the west ridge of Newtontoppen and a second ascent of Irvinefjellet via the ridge first climbed by Noel Odell and Sandy Irvine (which we have christened the ‘1923 Route’).

Not the average scene in Terminal 2. The journey to Svalbard began with a 6 hour flight via Oslo to Longyearbyen, ably facilitated and organised by major sponsor DialAFlight.

Longyearbyen, 78°N. Located mid-way between the Arctic circle and the North Pole, we arrived into the miniature capital of Svalbard at 1am to bright sunshine.

Trying to escape the reality of 18 hours at sea in the storm-wracked Arctic Ocean. Throughout the final 400km boat journey it was continually uncertain whether we could actually reach our starting point on the East Coast. Despite gale-force winds and high seas, the professionalism and skill of the Spitsbergen Guide Service saved the day.

After finally dropping anchor in the Hinlopen Strait at 4am, it took 3 hours to ferry equipment by rib onto the glacier at Duym Point.

First camp on the ice cap, established 93 years to the day after the 4 members of the 1923 sledging party disembarked from the SS Ternigen.

One of many obstacles hindering progress inland.

‘…our fortunes were baulked in a startling fashion. The valley… was wholly impassable. From each wall the ice fell away in dilapidated terraces… crazy pavements were piled high with a wild confusion of square-cut blocks and columns. This scene of chaos told of the bursting of a glacier lake but recently filling the valley.’ – The Geographical Journal, 1923

Local guide and glaciologist Endre solos one of the ice towers rising out of the lake.

Stable weather and surprisingly firm snows enabled the team to cross the Loven Plateau in just 8 hours, a journey that took the 1923 party almost 5 days.

A Northern Fulmar circles above the Bear Bay Glacier. With the exception of sparse bird life, our journey was almost entirely devoid of wildlife, despite considerable preparations expecting the contrary.

Base camp at 600m on the Loven Plateau. We remained camped here for nearly a week in order to pursue re-photography and scientific objectives without the burden of 80kg pulks.

Expedition historian Jamie and medical officer Will work on identifying the potential locations of photos from the 1923 expedition.

After nearly 40km the Bear Bay Glacier plunges into the Hinlopen Strait. We succeeded in drone-mapping 3 detailed transects across the glacier in order to compare them against earlier surveys taken from the air.

On the summit of Poincaretoppen. Known to Frazer and Odell as ‘Mt Deception’ due to their uncertainty over its identity, it’s a nickname which reflects the absence of cartographic resources available to the 1923 expedition.

A lightweight Nordic ski touring set-up made for rapid progress on the flat and uphill but required care going downhill without the security of a heel-binding.

After a chaotic and crevassed descent down from the Loven Plateau we were glad to make camp on safer ground en route to the Atomfjella mountains.

Bris, our beautiful German Shepherd – Alaskan Husky cross. Faithful polar bear watch and least objectionable member of the team.

The Veteranen glacier cleaves Eastern Spitsbergen in two, separating the snowy plains of the Loven Plateau from the Alpine peaks of the Atomfjella. Some half-a-dozen meltwater channels had to be laboriously portaged making progress less than straightforward.

Shrouded in the ethereal mist of a temperature inversion, Veteranen provided an eerie calm prior to our arrival in the ‘Atomic’ mountains.

Batman in the Atomfjella: Liam likened the towering spires of Junofjellet to Gotham City’s favourite vigilante.

James negotiates steeper ground on a ski-mountaineering foray into Tryggvebreen in the heart of the Atomfjella.

The route rises directly to the summit via the spectacular south east ridge, first climbed by Noel Odell and Andrew Irvine.

Belaying during an abortive attempt on the north ridge of Vestafjellet. Having spent the whole day searching for a route, we finally settled on our objective at 5pm only to abandon it three hours later due to poor rock and slow progress.

Evening light over the Atomfjella.

‘…one huge rock peak rose steeply to a sharp gendarmed spitze, in appearance very like the Italian side of the Matterhorn and looking impregnable from the East side…the scene was one as fine as any amongst the highest Alps.’ – Noel Odell, Journal

James battles gale force winds to recover equipment in the midst of a sudden storm on Gallerbreen.

After 18 hours pinned down by blizzards we emerged to blue skies and almost a metre of fresh snow partially burying our pulks.

Jamie tucks into breakfast courtesy of Expedition Foods. Even with dehydrated rations, food weighed in at around 40kg per person for 32 days.

Leaving the Atomfjella for the Chydenius mountains further south with Irvinefjellet in the background. The ‘1923 Route’ is the prominent ridge curving rightwards from the left summit down to the glacier.

Camped beneath Newtontoppen, Svalbard’s highest peak at 1,713m. On the right of the picture the attractive line of the unclimbed west ridge had caught our attention.

Snuggling down for another Arctic storm. With Force 11 winds threatening to rip the tent, we were forced into the survival shelter for nine chilly hours.

Home for five weeks. For several nights we relied on improvised struts to reinforce the tent against the storm.

The ‘Citadel’ – discovered and named by the 1923 expedition. Given a rare spell of clement weather the 120m granite face holds incredible potential for ambitious new rock routes.

Liam, director of photography, heavily laden with camera equipment.

As Liam’s co-director, Jamie reviews interview footage from the comparative shelter of the tent. Filming in the Arctic environment posed a number of unique challenges, not least keeping warm whilst hanging about for long periods.

Moonrise over Mt Chernishev. Just after midnight on 24th August the sun set for the first time in three months, signalling a comparatively rapid descent into winter and total darkness. Over the next week, we were rewarded with ever-lengthening sunsets.

Following our arrival at the summit of Chernishev we were amazed to discover an original note from 1923 folded into a thermometer case left by the 1901-2 Swedo-Russian survey.

Skiing downhill with a fully laden pulk took some getting used to. The team heads towards Lomonosovfonna and the ‘central ice basin’ where the ice reaches 600m in depth.

After several days of non-stop pulking we arrived at the vast Nordenskiold Glacier and the final obstacle guarding the West Coast.

Fed directly from the central ice basin, Nordenskiold tumbles sharply into the sea in a maze of gaping crevasses and hummocky ice. It took three days to travel a distance of little more than 10 km. Sometimes the best tactic was to caterpillar along meltwater streams with the pulks in tandem.

Fixing ice screws to lower the pulks down the last steep section of the Nordenskiold Glacier.

After thirty two days without a proper seat, we were delighted to finally reach the West Coast and pick up by the Spitsbergen Guide service.

Exhausted but happy the team returns to Longyearbyen Harbour after a successful expedition.

All photos by Spitsbergen Retraced/Liam Garrison.

To read more about Spitsbergen Retraced, please visit their website, Facebook, Twitter or Instagram.