Tying together February’s LGBTQ+ History Month and March’s Women’s History Month, Somerville JCR LGBTQ Rep Lucy Pollock (2023, History) spoke to alumna and Alumni Relations Executive, Jackie Watson (1986, English) to hear about College’s more recent lesbian history. After Somerville, Jackie went on to become a teacher and a Head of Sixth Form, before returning to Somerville as part of the Development team. They spoke about Section 28, Thatcher’s premiership, and what it was like to be a lesbian at Somerville in the 80s…

Somerville students on a political protest, 1983. Source: Somerville College archives

Back in the 1980s, Somerville was still a women’s-only college, but it was an era when colleges had largely mixed in Oxford, a process beginning in 1974. In fact, Somerville was one of the last remaining single-sex colleges, with just St Hilda’s remaining women-only once Somerville went co-ed in 1994. Despite staying single-sex, Somerville in the 80swas much less strict than in its early days. Jackie says it felt like any other college, just with female accommodation and female fellows. The first in her family to go to university, Jackie chose Somerville because her English teacher had been a Somervillian. She’d not quite expected the inclusive atmosphere that Somerville has become so well known for. Coming from a working-class background in Yorkshire, Jackie was pleasantly surprised by the diversity of her fellow undergraduates: an important aspect of the welcoming feeling of Somerville. This also applied to being a lesbian.

Jackie ‘came out’ to her parents at around sixteen, but says she probably knew that she had feelings for women whilst still in primary school. Her parents wanted her to be happy, and her mum encouraged her to keep it hidden, worrying that Jackie’s sexuality would decrease her chances of success. It was at Somerville that Jackie realised that some things should not be hidden, and at Somerville that she became out and proud about her sexuality. This was to become an issue again, though, when she first became a teacher: she was uncertain how open she could be in the political climate of the early 90s. Eventually, she realised that if she wasn’t open about her sexuality, how could she expect her students to come to terms with theirs?

At Somerville, her lesbianism was more political than an emotional choice: “being gay was, in a way, part of a wider feeling of being anti-establishment.” She felt that it was important to fight for the rights of the suffering LGBTQ+ community, and became a member of GaySoc (now OULGBTQ+ Society). There were a number of lesbian relationships within Somerville, and Jackie says that she never came across much antagonism, despite a mix of political beliefs within college.

Although some students chose to continue to live out in the third year, as well as the usual second year, perhaps feeling they could act more freely out of College, Jackie did not feel that Somerville was homophobic: indeed, it was a feminist haven against a pervasive cultural misogyny. In the 80s, female scholars throughout Oxford, as elsewhere, were fighting for the wider recognition of women as literary figures. Many female authors hadn’t been part of the core curriculum until then, and, as an English undergraduate, Jackie was pleased to see this broadening. At Somerville, the majority of students thought of themselves as feminist – something Jackie feels is more problematic for younger generations. She says that “nothing’s disappointed me more, as a Head of Sixth Form, than seeing my sixth form students hesitate to call themselves feminists.” Yet the feminism at Somerville was not necessarily found throughout the University, not even in GaySoc.

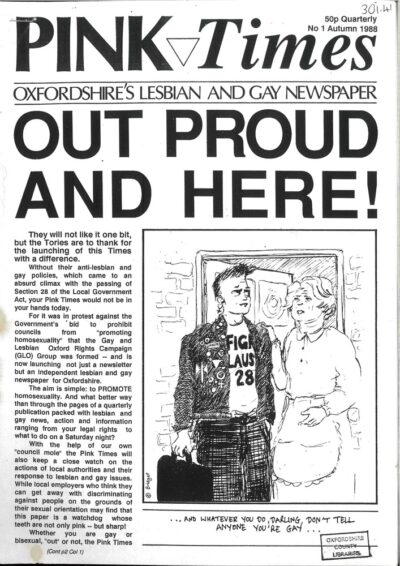

Gay and Lesbian Oxford Rights Campaign, “Cover of Pink Times issue 1, Autumn 1988,” Museum of Oxford – City Stories, accessed March 11, 2025, https://museumofoxford.omeka.net/items/show/664. The Pink Times was started in direct response to Section 28.

The women’s rights movement and the gay liberation movement in the 1960s and 1970s had strengthened one another, with lesbians often involved in both. But when the AIDS epidemic hit, inevitably gay movements focused on men’s issues. Lesbians were the least likely group to get HIV from sex, and so it was the gay male community which was hit particularly hard. The AIDS epidemic and the rising visibility of gay men across society in the 80s led to homophobia. Only two decades earlier, in 1967, gay sex had been decriminalised, but many across the world framed AIDS as a punishment from God, and wanted to refuse medical help to gay men. Lesbian relationships had never been criminalised, and this meant, Jackie says, that male gay relationships were disapproved of in a much harsher way. But homophobia affected the entire LGBTQ+ community. Jackie remembers being barred from giving blood as a lesbian student, as even medical practitioners thought of AIDS as a “gay disease”; it would not be fully understood for a number of years. Whilst Jackie of course did not blame GaySoc for focusing on the impact of AIDS, she was aware that women were not the centre of the fight. The focus was on men – understandable in their time of need.

The issue facing gay men was clear, but I ask Jackie what issues faced lesbians. Her answer: the fear of disappearing. She tells me that “people on the right of politics used to talk about ‘having their noses rubbed in’ the fact that people were gay… but they needed to know, because otherwise, we just disappeared”. This was something she felt particularly affected lesbians, who were “less visible”, and so more at risk of disappearing. Only a few generations earlier, in 1921, Parliament had decided that criminalising sex between women would only make lesbianism more visible, and that it was better to allow lesbianism to fade into the background, unacknowledged. But the women of the 80s would not let lesbians fade away. As an English student, Jackie was focused on literature, and felt it was partly through literature that lesbianism could become more accepted. Indeed, as publishers such as Virago published more books by women, they also brought into print books by current lesbian authors, and by those of the past; The Well of Loneliness, for instance, by Radclyffe Hall, was reprinted in the early 80s. This was one way to keep lesbians from disappearing in the face of legislation brought forward by the Tory government in power.

Section 28 (or Clause 28, the name Jackie refers to it by: a hangover from years of protesting against the legislation) was designed to make the legacy of LGBTQ+ people disappear. Jackie knew she was going into teaching, and so Section 28 gave her real cause for fear; it was intended to prevent gay teachers from “promoting” homosexual relationships in schools, but this really meant a prevention of discussion, and put a stop to teachers being themselves whilst teaching. If teaching about homosexuality was banned, how would a homosexual teacher fare? Section 28, Jackie felt, sought to negate people’s ideas of themselves. I can feel the anger and fear that being queer under the Act must have caused as she says, “You think history is progressive, moving forward all the time… but it felt like we weren’t making progress – if anything, Clause 28 felt like it was sending us backwards, and that all the freedoms and liberties that my generation had gained, future generations that I was teaching wouldn’t have.” As a history student, as an average person looking at America at the moment, the idea of history being progressive has played on a loop in my head since this conversation.

The idea of Margaret Thatcher being responsible for Section 28 is something I have personally grappled with, and it is fascinating to hear Jackie’s thoughts on the former Somervillian and former Prime Minister. “I like to think of Margaret Thatcher as two people joined together,” Jackie says. There was an immense pride within Somerville in the woman who showed that women could succeed in politics, that a woman could obtain the country’s highest elected office. Jackie also acknowledges that “we owe her a lot”. She remembers seeing Thatcher at college frequently, as the Prime Minister did a lot of fundraising with then-Principal, Daphne Park, who had herself graduated from Somerville in 1943, a few months before Thatcher matriculated. Thatcher put Somerville on the map and her influence and fundraising has helped subsidise costs for generations of students; at the same time, her policies related to sexuality seemed to cut against the inclusive ethos of her former college. Jackie respected her as a feminist; she protested against her as a lesbian. Somerville will always be proud of the first female Prime Minister in the UK, but that legacy jars with Section 28 in a way that can still be felt today.

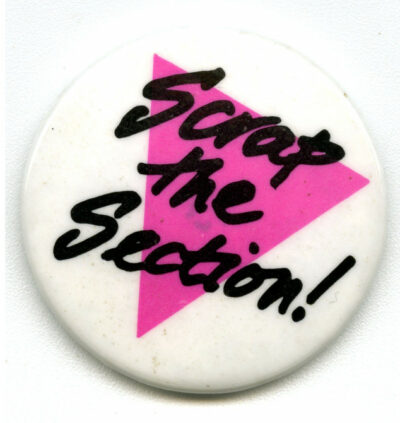

Badge from the 80s, held by the Bishopsgate Institute.

Section 28 prompted a lot of protest, something which is relevant again today. “We were marchers in the eighties”, Jackie says, discussing how JCR banners used to be paraded on marches. It was a very vocal protest: shouting and marching. She remembers sympathetic feelings from local politicians and the town, and an unsurprising lack of sympathy from The Oxford Union, who would frequently host figures with homophobic views (“another chance for marching and shouting!”). Students have always protested, and Jackie says that “it’s important that young people stand up for what’s important to them in their generation.”

Jackie calls herself “very lucky” – “I’ve always lived a mainstream life,” she says. But protesting against Clause 28, being out and proud in a time when people want you to disappear – I’d say this is far from mainstream. I’d also say that what Jackie has is not luck – it’s resilience. Jackie has made the choice over and over throughout her life to never stay hidden. There is a certain privilege in even being able to write this article, in being able to study the history of sexuality, especially at a time when equality and diversity initiatives are being scrapped by corporations and governments. Jackie saw the right to teach about homosexuality taken away despite her protests, despite fighting to stay visible. The atmosphere and freedom that Somerville has now is a legacy of the students of the eighties, the students who fought against Clause 28. The inclusiveness that has made Somerville feel like home for hundreds of us is the legacy of every student who came before us. The women who pursued lesbian relationships despite fears of antagonism, the students who walked around wearing pink triangles to show their support, the gay and straight students who showed up for marches: it is the legacy of these students that has shaped Oxford into the place it is today. It was the actions of these students that allowed history to continue progressing, even when those in power tried to force it to regress.