Welcome to the second part of our series on Somerville’s lesser known LGBTQ+ history, written by students for LGBTQ+ History month. Zoe Byrne (2023, Philosophy and Linguistics) introduces the lives and work of Iris Murdoch and Philippa Foot.

Philippa Foot at Somerville

Iris Murdoch and Philippa Foot became close friends in 1939 while studying at Somerville. They were brilliant and defiant women, who began their journeys into philosophy in a period when many male students were away at war. Metaphysics and ethics — their respective specialties — had become increasingly unpopular in Oxford in the 1930s, with the leading British thinkers at the time being logical positivists who dismissed abstract questions of being and knowing. There was a male-dominated custom of analytic philosophy which dismissed discussions of ethical values as meaningless and unverifiable, instead focusing firmly on language and facts. Talk of moral obligations was reduced to nothing more than an expression of opinion or disapproval.

But there was a war on, and it was more apparent than ever that society could no longer sideline its moral values. Foot chose to explore these values by embarking on an academic career, taking a teaching post at Somerville and becoming the college’s first philosophy tutorial fellow in 1949. Over the course of her career, she would be a front-runner in the shift from what makes an isolated action bad, to what makes a person good. She argued that morality is about how to live; it is the endeavour of our lifetimes to become the sort of person who habitually and happily does virtuous things. For Foot, to be virtuous is to be well-rounded and human.

Foot had some very important views on salient topics of the day. Her widely-cited ‘Trolley Problem’ was used to discuss moral permissibility in her influential 1967 paper The Problem of Abortion and the Doctrine of Double Effect, and it remains hugely relevant in ethical discussions to this day. Her rejection of the “rigoristic, prissy, moralistic tone” of previous ethical discussion, which prescribed grand rules and so-called objective duties, let her focus on why it truly matters that we behave in virtuous ways.

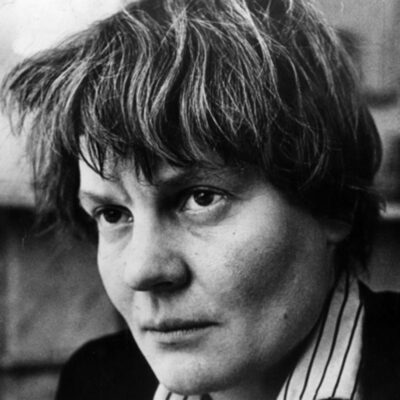

A young Iris Murdoch

Murdoch also put a great focus on the nature of good and evil, focusing throughout her novels on the metaphysics of morality. In her Costa prize winning 1974 novel The Sacred and Profane Love Machine, and her Booker prize winning 1978 novel The Sea, The Sea, Murdoch explores sexual relationships, spirituality, and what love might be. She developed an entirely distinctive position on the philosophy of art and religion, both of which she saw as important for morality.

Not only were Murdoch and Foot bold in philosophy, they were bold in life. Despite originating from an aristocratic family (being the granddaughter of President Grover Cleveland), Philippa Foot was a lifelong socialist and Labour Party supporter, and was an atheist and a key early member of Oxfam. In 1956, she was one of only four academics to vote against Harry Truman, the U.S. president responsible for Hiroshima’s devastation, receiving an honorary Oxford degree. Iris Murdoch was described as being “wild and bohemian”, being a former member of the Communist Party (although she later rejected Marxism) and having multiple affairs with men and women throughout her marriage to the Warton Professor of English John Bayley. The most notable of these relationships was with her lover and lifelong friend, the writer Brigid Brophy.

Murdoch and Foot both had relationships with men and women, lived together at various points and had a brief affair in 1968. Their physical entanglement ended, but they remained close friends for decades after, and it’s clear from letters that their fondness for each endured, even during the fifteen year period in which they had little contact. After a severe falling out in the 1940s, in which Murdoch hurt her friend badly by becoming involved with Foot’s lover, she found herself alone and guilty, which demonstrably impacted her writing and thinking — her novels often discussed the intersection of morality and relationships, and in particular love and ego. The two reconciled after Philippa’s divorce from historian Michael Foot, alongside an apology from Murdoch and a confession which proclaimed that her love for Foot remained as “deep and tender as ever – and always will remain.” She told her, “My dear heart, I love you.”

The nature of their relationship was not a sexual one after their 1968 affair, with Iris referring to Philippa as her “lifelong best friend”, but it was intensely personal and enduring. They were close for sixty years, and when Murdoch eventually succumbed to Alzheimer’s, her friend was one of the only people she wished to see. It was a fluid and queer relationship, and their friendship is not any less important for lacking the eroticism of a romance. Instead, the joy that two undaunted, genius women found in decades of love should be celebrated this LGBTQ+ History Month. Our predecessors have so much to offer us in wisdom, in ethical proclamations from Foot and twenty-six novels on love from Murdoch. As a queer woman studying philosophy at Somerville myself, who grew up in Iris Murdoch’s childhood hometown of Chiswick and can almost see the blue plaque on Philippa Foot’s Walton Street home from my bedroom window, I feel their legacy every day.