Anyone who has read Vera Brittain’s Testament of Youth, or paused to read the plaque at the front of College about the military hospital based here, knows that Somerville College had a significant role to play in the Great War.

Less well-known, but equally impactful, is the contribution made by Somervillians during World War Two. For Remembrance Day 2024, therefore, we have decided to celebrate five Somervillians who made significant contributions during WWII in their respective fields. There must be many more such stories of Somervillians contributing to these historic moments of adversity and struggle, so we are encouraging everyone to get in touch with their stories of Somervillians who contributed in both World Wars, in order that we might create a miniature archive of these stories for posterity. To share your story, please email development.office@some.ox.ac.uk

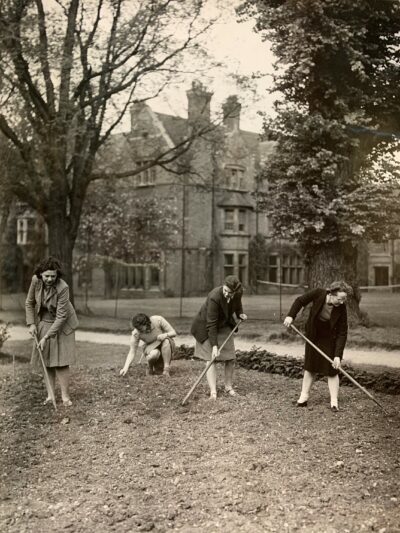

Janet Vaughan: Scientist

(b.1899, matric. 1920)

Before becoming Principal at the end of the Second World War, Janet Vaughan had already built an international reputation as a research scientist. She had also seen herself confirmed as a dyed-in-the-wool socialist by the experience of caring for working-class communities in North London. In the latter half of the 1930s, Janet Vaughan directed her energies to procuring and sending supplies to the Communists in the Spanish Civil War. Her involvement in this conflict was the genesis of her first great contribution tothe Second World, as it alerted her to the need to store blood for war casualties. Consequently, Vaughan and her colleagues at Hammersmith Hospital led the process to refine blood storage and transfusion techniques, which in due course left to the creation of the system of blood donors and blood storage across the capital that would prove vital in the treatment of patients during the Second World War. Vaughan was in charge of the Slough depot, where the refrigeration units to store the blood were next to the bar – useful if she needed extra donors in an emergency – and ice-cream vans were requisitioned to help with the distribution.

Before becoming Principal at the end of the Second World War, Janet Vaughan had already built an international reputation as a research scientist. She had also seen herself confirmed as a dyed-in-the-wool socialist by the experience of caring for working-class communities in North London. In the latter half of the 1930s, Janet Vaughan directed her energies to procuring and sending supplies to the Communists in the Spanish Civil War. Her involvement in this conflict was the genesis of her first great contribution tothe Second World, as it alerted her to the need to store blood for war casualties. Consequently, Vaughan and her colleagues at Hammersmith Hospital led the process to refine blood storage and transfusion techniques, which in due course left to the creation of the system of blood donors and blood storage across the capital that would prove vital in the treatment of patients during the Second World War. Vaughan was in charge of the Slough depot, where the refrigeration units to store the blood were next to the bar – useful if she needed extra donors in an emergency – and ice-cream vans were requisitioned to help with the distribution.

Just before the war ended, Vaughan became one of the first civilians to follow the British army into the concentration camp at Belsen. Her job was to work out a treatment for extreme cases of starvation, using concentrated protein in liquid form – protein hydrolysate. Her work was difficult, not least because her patients were terrified of the sight of her with a needle: the Nazis had injected their victims with paraffin to make their bodies burn better. She barely noticed VE Day as she continued her work. Returning to England with a plane full of casualties after the end of the war, Vaughan’s life was to shift markedly. Although she would continue her medical research throughout the next three decades, in the autumn of 1945 she moved back to Oxford to commence her tenure as Principal of Somerville.

Doreen Warriner: Humanitarian

(b. 1904, matric. 1928)

When Doreen Warriner (1904-1972) was played on screen by Romola Garai in the 2023 film, One Life, the world had the chance to see the role she played in the evacuation of hundreds of Jewish children from wartime Czechoslovakia. One reviewer suggested that Doreen’s story made such an impression that she seemed “more than deserving of her own movie.” In fact, Doreen Warriner is thought to have saved more than 15,000 refugees from Nazi persecution, including both Czech dissidents and Jewish children. For this, she was awarded the OBE in 1941 and, posthumously, the British Hero of the Holocaust Medal in 2018.

When Doreen Warriner (1904-1972) was played on screen by Romola Garai in the 2023 film, One Life, the world had the chance to see the role she played in the evacuation of hundreds of Jewish children from wartime Czechoslovakia. One reviewer suggested that Doreen’s story made such an impression that she seemed “more than deserving of her own movie.” In fact, Doreen Warriner is thought to have saved more than 15,000 refugees from Nazi persecution, including both Czech dissidents and Jewish children. For this, she was awarded the OBE in 1941 and, posthumously, the British Hero of the Holocaust Medal in 2018.

On paper, Warriner did not at first seem destined for a humanitarian. A first in PPE from St Hugh’s led her to embark on a PhD in German industrialisation at the LSE. She resumed her studies thanks to a Mary Somerville Research Fellowship in 1928, and it was during her time at Somerville that Warriner fell in love with Czechoslovakia, a relationship that was to prove momentous. When Neville Chamberlain signed the Munich Agreement in 1938, Warriner abandoned her plans to go to the US on a Rockefeller Fellowship and instead flew to Prague. ‘I had no idea at all what to do,’ she later wrote, ‘only a desperate wish to do something.’ She began writing frustrated letters to the Telegraph and Guardian about camp conditions, stressing the need for ‘visas not chocolate’. So began eleven months of desperate work in which Warriner headed the Prague office of the British Committee for Refugees from Czechoslovakia. She later said, ‘Every day the planes were full of the well-to-do going to London, sponsored by their friends and knowing how to push. I felt bound to say something on behalf of the people who could not push.’ And push she did. Aided by Nicholas Winton and Somervillians including Jean Rowntree and Somerville’s first MB Eleanor Rathbone, she saved the lives of thousands.

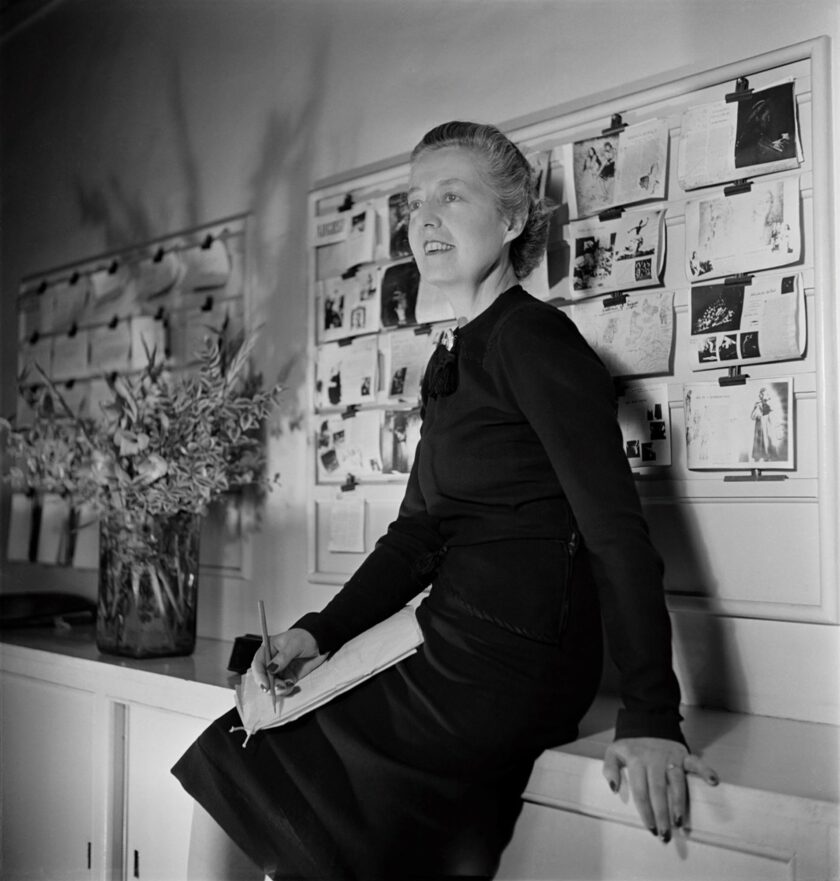

Audrey Withers: Journalist

(b. 1905, matric. 1924)

Editor of Vogue for twenty years from 1940, Audrey Withers recently featured in the biopic Lee, about the famous photojournalist Lee Miller. As Miller’s editor, Withers led the magazine through the Blitz and ensured that Miller’s stories from Nazi-occupied Europe reached the public. Left-leaning, highly intellectual and always outspoken, Withers was not naturally interested in fashion – but she made herself a good judge of it. Her real passion was journalism, good writing and features. It was these qualities alongside an extraordinary determination to keep going under any circumstances which she brought to her editorship of Vogue. By the end of 1940, when London had been bombed for 56 nights in a row, Withers could be proud that she had managed to get the October, November and December editions of her magazine out almost on time. By 1944 the President of the Board of Trade, Hugh Dalton, described her as the most powerful woman in London.

Withers always put her ability to cope with difficult situations down to the experience of Oxford’s tutorial system, acquired reading for PPE from 1924. She said later of her tutorials: ‘One is out in the open and compelled to draw on one’s powers. Intellectually, it is the equivalent of a sports training and equally necessary to get good results.’ There is no doubt she drew on that training and the experience of her three years at Somerville when things got tough at Vogue.

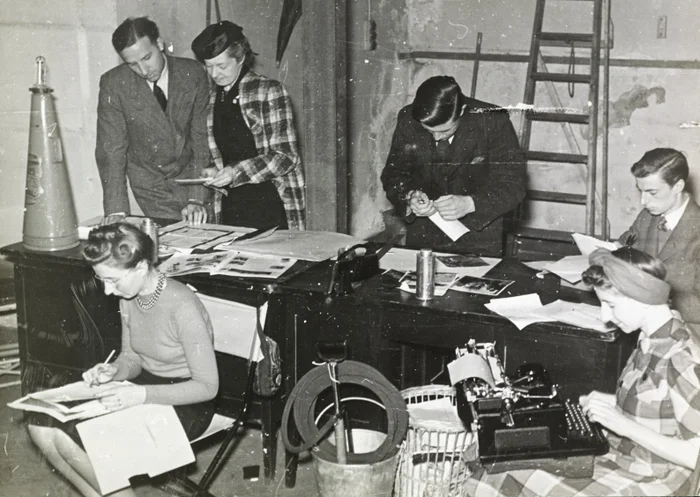

Daphne Park: Espionage

(b. 1921, matric. 1940)

The second College Principal who made a marked contribution to the progress of World War 2 graduated from a Languages degree in 1943. Daphne Park had been to France during her three years at Somerville, to improve her fluency, and as she left Oxford she was determined to use her skills in the fight against Nazism. Turning down job offers from the Treasury and the Foreign Office, she made the decision to join the FANY: the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry, established in 1907, was not only active, of course, in the nursing field. It had, during both world wars, also conducted intelligence work. Taking the entrance tests for the FANY, Park came to the attention of those running the Special Operations Executive (SOE), and her coding skills, alongside fluent French, appealed to the secret organisation set up by Churchill to sabotage the Nazi war effort. Promoted to the rank of Sergeant, Park worked with operatives tasked to support the French Resistance, and led coding training: teaching them about wireless, codes and communications.

At the end of the war, as the SOE was dissolved, Park determined to continue in the world of intelligence work. Sent to Vienna in 1946 to find Axis scientists and convince them to work for the British, she was recruited by the Secret Intelligence Service, for whom she worked for more than thirty years. After postings across the world, from Moscow to Hanoi, she retired from SIS’s most senior operational rank, Controller of the Western Hemisphere. In 1979 she returned to Oxford and became Somerville’s Principal.

Pat Davies (née Owtram): Code-Breaker

(b. 1923 – matric. 1951)

One of our most recent Honorary Fellows is Pat Davies (née Owtram and pictured here with her sister Jean). As a young woman during World War Two, Pat Owtram did vital secret work manning covert listening stations on the South Coast, for which she would later receive the Légion d’Honneur, France’s highest order of merit.

Pat gained her linguistic skills as a teen, when her family employed a Jewish refugee, Lily Getzel, as a cook after she escaped from Austria. On finishing school, Owtram served as a special duties linguist in the Women’s Royal Naval Service, listening to radio transmissions in both German and encrypted code, transcribing and decoding the messages and passing them on to Bletchley Park. Later in the War she worked for the Supreme Headquarters of the Allied Expeditionary Force in London, under General Eisenhower, scanning German official documents to search for potential war criminals. She was offered a job as a translator at the Nuremberg trials, but chose to go home to be with her father who had returned after surviving his ordeal as a POW. Unknown to her at the time, her sister, Jean Argles, had also been a wartime codebreaker and member of SOE. Later they were to join together to write their popular memoir, Code-Breaking Sisters.

After the war, Pat returned to education, gaining a first from St Andrews and a B.Litt from Somerville before travelling to Harvard for a study fellowship. She later became a journalist and worked in television, developing programmes such as University Challenge and The Sky at Night. Now more than 100 years old, Patricia describes herself as the only centenarian in Chiswick who knows how to use a Sten gun.

Further reading:

- Janet Vaughan: Bloomsbury, Belsen, Oxford by Sheena Evans (Chester University Press, 2024)

- Dressed for War: the story of Vogue editor Audrey Withers, from the Blitz to the swinging sixties by Julie Summers (Simon and Schuster, 2020)

- Queen of Spies: Daphne Park, Britains Cold War spy master by Paddy Hayes (Duckworth, 2016)

- Code-Breaking Sisters: Our Secret War by Patricia and Jean Owtram (Mirror Books, 2020)