Somerville’s lecturer in Early Modern History, Dr Oren Margolis, writes about two early books, printed by Venetian Renaissance publisher Aldus Manutius, that have entered the library. The books come from the collection of the late Professor of Comparative Philology and Fellow of the College, Anna Morpurgo Davies.

Somerville’s lecturer in Early Modern History, Dr Oren Margolis, writes about two early books, printed by Venetian Renaissance publisher Aldus Manutius, that have entered the library. The books come from the collection of the late Professor of Comparative Philology and Fellow of the College, Anna Morpurgo Davies.

2015 was the 500th anniversary of the death of Aldus Manutius, the most famous printer of the Italian Renaissance and a towering figure in the history of scholarship and of the book. Three Somerville History undergraduates assisted me in curating an exhibition celebrating his achievements at the Bodleian Library (Aldus Manutius: The Struggle and the Dream) and put on their own one-day display to coincide with the official launch, drawing from Bodley’s extensive collection. Oxford colleges are rich in Aldine books as well. But until the end of 2015, Somerville was unfortunately among those without any books printed by the Aldine Press during its founder’s lifetime (though a first edition of Castiglione’s Book of the Courtier, printed by Aldus’s heirs in 1528, has made a number of surprise appearances in tutorials). All that changed when the College received two Aldines – the gift, along with her much larger collection of antiquarian books, of the late Professor of Comparative Philology and Fellow of the College, Anna Morpurgo Davies.

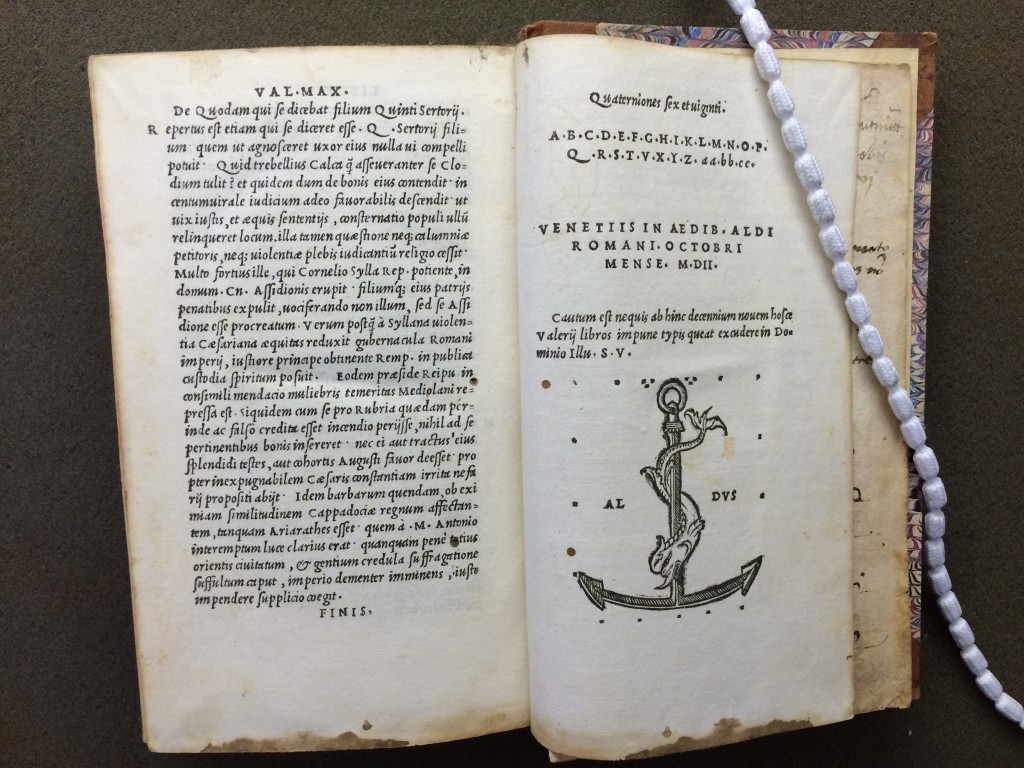

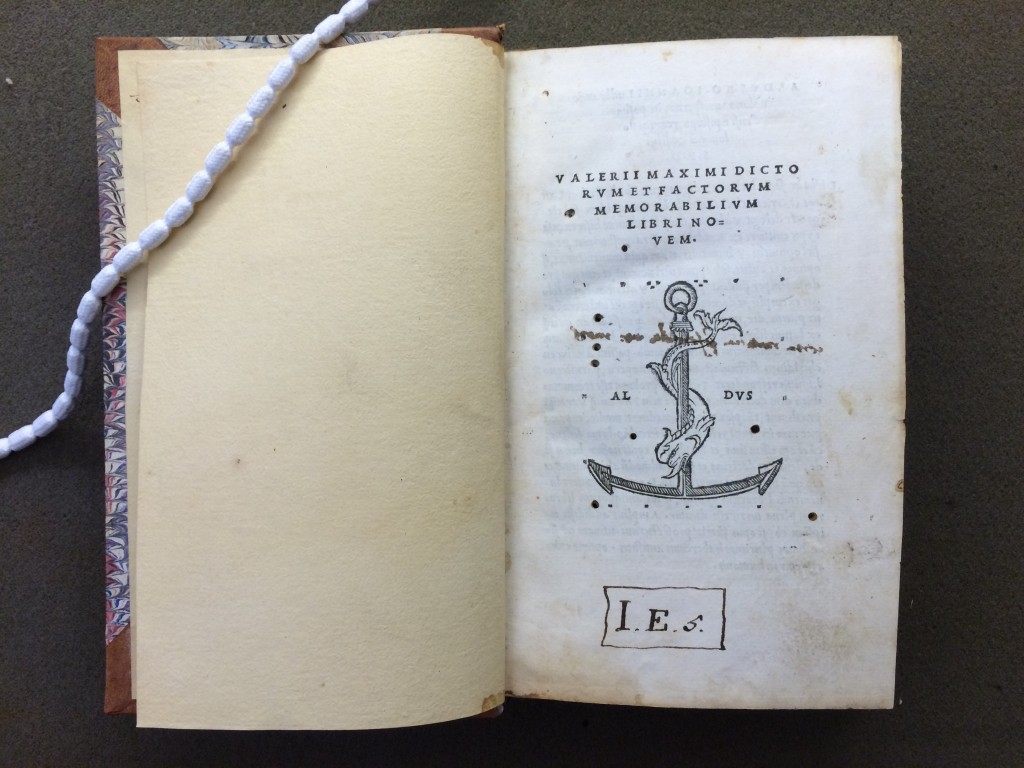

The books are characteristic of Aldine publishing: classical texts printed in octavo (pocketbook format) and in italic type – both innovations of Aldus – and adorned with his famous ‘dolphin and anchor’ device. The first one, the 1502 edition of the Roman poets Catullus, Tibullus and Propertius, is also indicative of changing tastes: Catullus is missing, quite probably because a post-Renaissance owner found his verses a little too racy. (Evidence of prudishness is all too common when researching Aldine books: there are many copies of the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili where, in a woodcut of the rites of Priapus, the god has suffered a prominent part of his anatomy to be blacked out.)

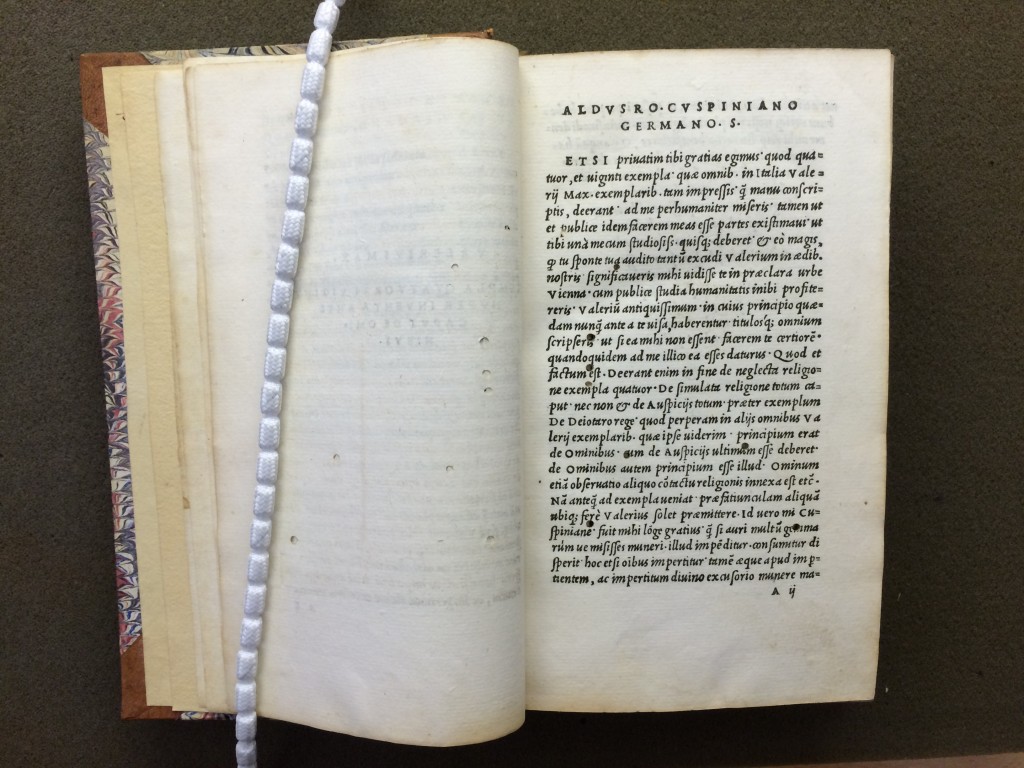

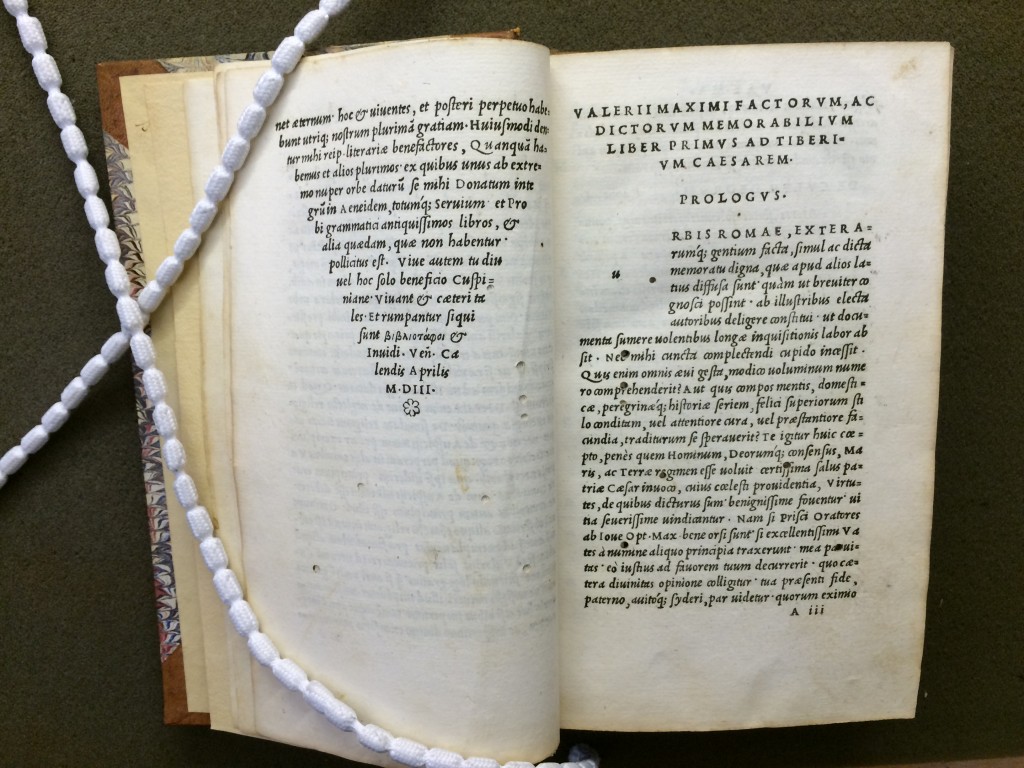

The other volume, the ‘memorable sayings and deeds’ collected in the first century AD by Valerius Maximus, is more interesting for what it tells us about Aldus’s practice as an editor and publisher, the Venetian printer’s international reach, and the collaborative ideals of the humanist enterprise. Aldus first published Valerius Maximus in 1502, dedicating it to the bishop of Poznań in Poland, Jan Lubrański. But then, after the Viennese humanist Johannes Cuspinianus sent him some missing exempla found in other manuscripts, Aldus reprinted the text the next year with this new material appended and an additional dedicatory letter to Cuspinianus (though with the same 1502 colophon). From this, we learn something very important about how Aldus conceived the role of the new technology. The printed word was not the final word: rather, it was a tool for the propagating of texts so that good editions would proliferate and errors could more quickly be corrected.

Cuspinianus, meanwhile, was a leading figure at the University of Vienna and in the humanist movement in the German lands more broadly; he was also a courtier and diplomat of the Emperor Maximilian, and would be one of the negotiators of the 1515 double marriage between the Habsburgs and the Jagiellonians (the east-central European royal house that is the subject of Somerville Fellow Natalia Nowakowska’s major research project). Before that, however, he led the efforts supported by other German humanists who had frequented Venice to bring Aldus to Austria to set up an Academy under Maximilian’s patronage – though, like so many plans depending on Maximilian, this one fell through. Still, we might read the exchange of manuscript and dedication between Cuspinianus and Aldus as a form of networking, by which the former gained from the Venetian’s élan and Aldus strengthened some potentially profitable connections. The copy of Valerius Maximus now at Somerville is the only complete copy in Oxford of the 1503 edition.

Renaissance humanists are often portrayed as opportunists and careerists, philosophically and politically uncommitted, but they were united by a different ideal: they believed in a renovation of society through the literary revival of antiquity. The humanists simply knew what all scholars nowadays are discovering: without support, there is no scholarship. If we misunderstand them, it is in part because we don’t like to look in the mirror too closely and consider what exactly our great ideals are.

None of this, however, was a surprise to Anna Davies. Like Aldus, she owed her intellectual formation to Rome, but then built her career elsewhere. The Renaissance philology practiced by Aldus and his colleagues involved correcting ancient texts and even debating the pronunciation of classical Greek; they were fascinated by mysterious scripts and undeciphered languages. Prof. Davies produced the first-ever lexicon of Mycenaean Greek, which language was written in Linear B, and was an expert in the languages of ancient Anatolia, deciphering the Luwian hieroglyphics.

She also published extensively on the history of philology, and, with this strong sense of its past, became a tireless promoter of her discipline. She inherited a subject whose future in Oxford was uncertain; she left it with the chair endowed in perpetuity. Yet none of this would have been possible without her efforts to secure the real foundations of that future, the generations of students she supported. Colleagues who tell me of her office overflowing with books – so much so that she even had to colonize nearby rooms to house them all – bring to my mind the highest praise of Erasmus for his friend and mentor: ‘Aldus is building a library which knows no walls save those of the world itself’.

When Thomas More wrote his Utopia (a work celebrating its own 500th anniversary this year), he told of how the denizens of that island needed only be shown some books printed by Aldus and had the process generally described for them to discover and perfect for themselves the entire art of printing – so great was their love for learning. Printing may no longer be the art of the future – a development which, incidentally, would not have frightened Aldus in the least – but it is the history of the age of new media in which we live. New insights will doubtless follow the new perspectives our time allows. One looks forward to all the unanticipated consequences these books may have for the next generation of Somerville scholars and students.